My previous two posts (Studying the Skeleton, Studying Musculature) are quite lengthy, and may contain an overwhelming amount of information for some of you. Try as I may to keep things simple, drawing the human body is a complex process, with lots of moving parts.

So, with that in mind, I’d like to take a step back with this post, and focus on the basics – concepts that can be understood by everyone, including those who aren’t interested in drawing. Today, we’ll be talking about stick figures.

An Introduction to Stick Figures

In some ways, you could consider the stick figure a sort of baseline for figure drawing. It’s a basic ‘skeleton’ (in terms of a visual framework) for drawing the human figure.

For this reason, stick figures are super common among starting artists and amateurs alike. This is evidenced by a phrase that I’d wager almost every single artist (across various skill levels) has heard at least once.

I’m pretty sure even my mom has said this to me.

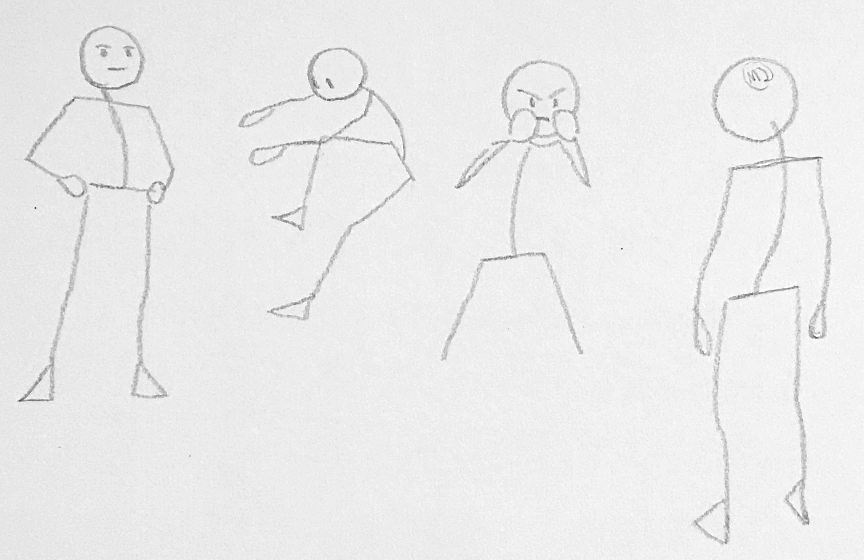

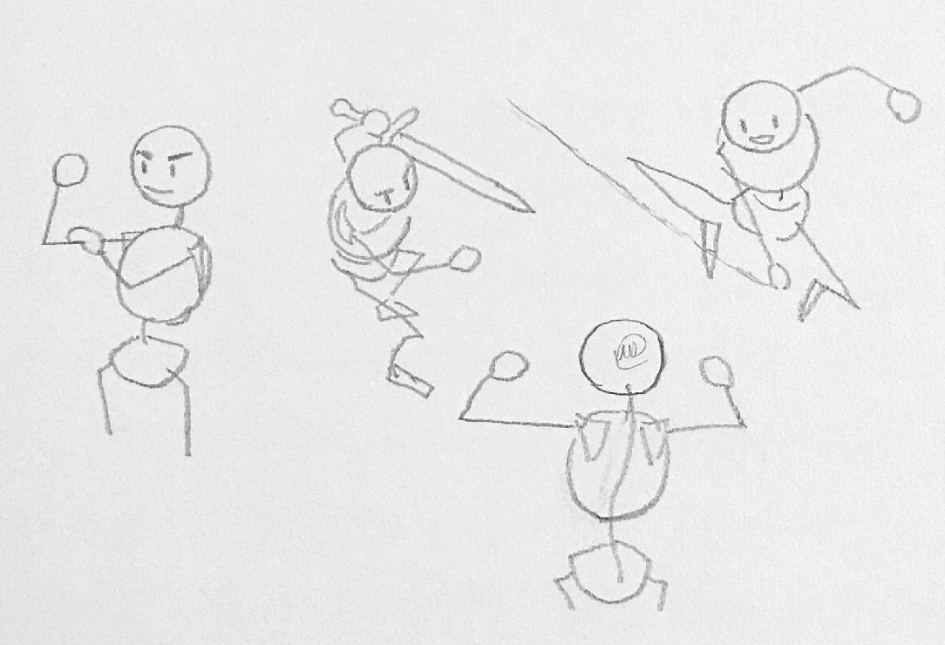

Believe it or not, stick figures are actually quite useful, even as you become better at drawing people. You can achieve a decent amount of expressiveness with basic stick figures, through exaggerated posing.

Like I said, stick figures provide a basic visual framework for posing and drawing the human figure. Rather than thinking about all of the bones, ligaments, muscles, and tendons of a particular body part (like the arm, for example), you can instead represent that complex structure with a single line.

However, by virtue of their simplicity, most stick figures drawn by beginner/amateur artists look unrealistic, and (at times) lifeless.

So, how can we make these stick figures look more realistic, without a ton of extra work?

Remember, our goal here is to keep things simple, while also improving the appearance of our stick figures. If things get too complex, it defeats the purpose of drawing a stick figure: providing that basic visual framework I keep bringing up.

In order to fix these mistakes, we first have to know what they are, so let’s talk about some of the common mistakes people make when drawing stick figures.

Common Mistakes

For starters, most stick figures have arms that start at the base of the neck. This is wrong. In some cases, these stick figures may lack a neck entirely.

Another common mistake is the torso being the longest part of the body. This is also incorrect.

Stick figures will also have legs which simply branch out directly from the body, at the base of the torso. The same could be said for the arms, which branch out from the body near the top of the torso.

In addition, these common stick figures will generally represent the arms and legs as singular lines. In reality, our arms can be divided into two sections (upper arm and forearm), and so can our legs (thigh and crus).

Along that train of thought, most stick figures will exclude hands and/or feet. This is, of course, inaccurate – hands and feet are extremely important parts of our anatomy.

For clarity, here’s the aforementioned mistakes written out in a simple list.

- Arms start at the base of the neck

- Neck may be missing entirely

- Torso is the longest part of the body

- Legs (and arms) branch out directly from the torso

- Arms and legs represented by one line

- Missing hands and feet

These mistakes are perfectly understandable, of course – they’re reasonable errors.

When drawing a stick figure, we tend to focus on the most ‘important’ parts of our body. In most cases, these would be the head, arms, and legs.

To that end, the middle portion of a stick figure (which vaguely represents the torso) is simply a place for the head, arms, and legs to originate from. Without that midline, those parts would just be floating in space, attached to nothing.

However, as evidenced by the fact that these are mistakes, they don’t accurately represent the human form.

Fixing those Mistakes

So, how can we fix these mistakes, without giving ourselves a ton of extra work? Well, as always, we should try to think logically.

Head and Neck

You need a neck, because neck muscles allow you to turn your head (among other things, of course). Without a neck, you would have to turn your entire body to look around, or search your environment for potential threats. Having neck muscles allows us to turn our head, without having to turn our body.

Arms and Hands

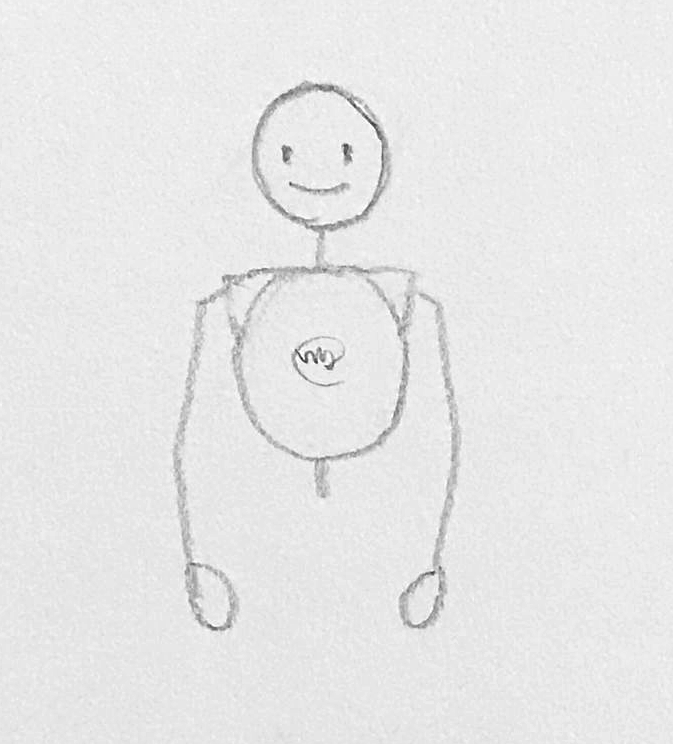

Along that train of thought, your arms don’t start at your neck. Your arms are attached to your body through a structure called the “shoulder girdle.” Let’s just draw a line for the clavicle (collarbone).

Now, to be clear, arms do not technically ‘start’ at your collarbone. As far as I’m aware, the humerus (upper arm bone) connects to your scapula, which then connects to your clavicle. Even though they’re closely related to one another, your scapula and clavicle are two separate structures.

Obviously, in this situation, that detail isn’t super important. For the sake of simplicity, we’ll draw a line for clavicle, and have our arms start there. Don’t forget to divide the arms into two separate lines – a circle or rectangle representing the hands will suffice.

Already, this is starting to look more realistic.

Torso

Now, we can draw a line for the torso. As mentioned in the previous section, your torso is not the longest part of your body. In reality, your torso is approximately 1/2 the entire length of your body (from head to toe). Please note that your torso should end above your hands.

In this case, the point of termination for our torso is a joint called the “pubic symphysis.” Anatomically, this joint is the half-way point of our body. Please note that the pubic symphysis is actually a part of your pelvis.

Hips and Legs

Much like your arms (which start towards the lateral edge(s) of your collarbone), your legs don’t just branch off from your torso – they start from your pelvis. The pelvis is one of the most complicated forms to draw, but since we’re focusing on simplicity, we’ll just be drawing a line to represent its width – as we did with the clavicle.

That saves us a lot of effort – drawing the pelvis is really hard.

The purpose of these two horizontal lines (representing the clavicle and pelvis) is to fix the ‘branch’ problem with common stick figures. In addition to providing a greater degree of realism to our stick figures, these lines make it easier to accurately render these body parts in perspective.

Now that we have a line representing our pelvis, we can attach the legs. Remember, we’re dividing the legs into two separate lines – just like we did with our arms.

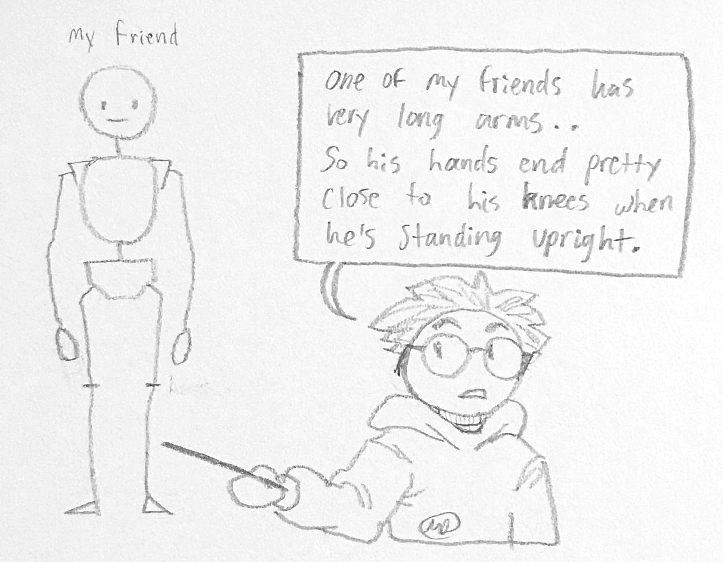

Note that the tip of your middle finger (lowest point of the hand) should end about halfway down your thigh. Keep in mind that this is a general estimate. Arm length varies pretty heavily, so that measurement isn’t going to be accurate for everyone.

Since we’re focusing on simplicity, general estimates are just fine. Once you’ve drawn the lines representing your legs, you can add the feet. Personally, I think triangles are the most accurate representation of your foot’s shape, but you can use rectangles or circles if you want.

All done!

Our New and Improved Stick Figure

And hey, look at that! We’ve got ourselves a finished stick figure. This drawing already feels more realistic than our original stick figure, and more clearly represents that basic visual framework I brought up earlier in the post.

Even though this stick figure already looks pretty good, we can make them look even better through the use of shapes.

Adding Detail through Shapes

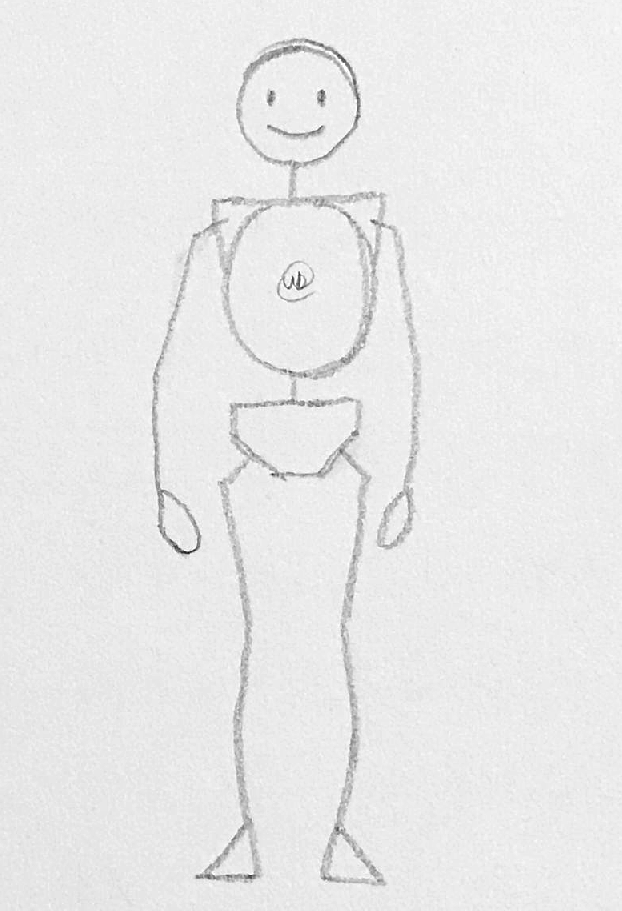

At the moment, our stick figure is.. well, pretty stick-like. That is, they’re lacking in mass. Even the skinniest people have what artists refer to as the “three major masses.”

These are important for figure drawing because they’re instantly recognizable, and help give a general idea of what sort of pose a person is in. Understanding the three major masses will make your figure drawings far more realistic.

Now, generally speaking, the three major masses are drawn as forms, which (as I’ve discussed in previous posts) are three-dimensional shapes. Since drawing 3D forms is a lot of work, we’re going to be simplifying them into 2D shapes.

Head (Skull)

Odds are, you’ve already drawn this one. Most stick figures will have at least one shape – a circle representing the head/skull. This circle is perfectly sufficient, so we won’t be adding any more detail to it.

In figure drawing, you’d usually draw a square or rectangle representing the mandible (lower jaw), but that’s not necessary for our stick figure.

Rib cage and Scapulae

We can use an oval to represent the ribs, with a triangle that represents the scapula on either side. Keep in mind that the scapula are located on the posterior (back) side of your body, so they should be slightly obscured by your rib cage.

We can then attach our arms to the scapula on either side, which makes things look a bit more realistic. Don’t forget to add the shapes representing the hands.

In this case, the top line of the ribs is basically just the line we used to represent the clavicle in the previous example. If you’d like, you can draw that clavicular line across the upper portion of the ribs, but that’s not entirely necessary.

Draw a line following your neck, representing your spine, at the bottom of the rib cage. This will connect with the pelvis shape, and helps create the illusion of overlap – which will give your drawing some depth.

Pelvis and Legs

Lastly, we can draw another shape representing the pelvis. Really, it’s up to you which shape you decide to use for this mass. An oval, rectangle, or inverted (upside-down) triangle would look fine.

In my opinion, the most accurate shape for the pelvis is an inverted trapezoid, but again, you can draw whatever shape you’re most comfortable with. I like using a trapezoid, because we can attach the femurs to the sloped edges on either side of the shape.

Now, in addition to adding some detail to the pelvis, we’re going to add some detail to the legs. In our previous drawing, the legs of our stick figure were straight lines. In reality, our femur (upper leg bone) slopes inwards, slightly. Our femur also has a “neck,” which we’ll be representing by a shorter line connecting the femoral line, and pelvis. Don’t forget to add the shapes representing the feet.

All done (again)!

Our New(er) and Improved(er) Stick Figure

With those final adjustments made to our figure, we’re done! (For real this time).

Even with these simple changes, our figure looks much more realistic. If you’ve been drawing along with me, you may find yourself surprised at just how easy it was to draw a more realistic stick figure. Drawing shapes and lines isn’t especially difficult, yet those simple shapes give life to your drawing(s).

Hopefully, you now feel more confident in your ability to draw stick figures. And as always, thanks for reading.

Disclaimer

All information in these posts is my own words, unless explicitly stated otherwise. None of this information is quoted, nor paraphrased, unless explicitly stated otherwise. Any similarities between my own words, and the informative sources/hyperlinks provided is purely coincidental, unless explicitly stated otherwise.

In any case where I am using someone else’s words (or imagery), the source will be cited internally, with a link to that source provided either within the internal citation, at the end of the post under “Sources,” or both.

March 14, 2021 at 4:34 am

I allows believed that the stick figure odd and does not represent a person. I agree that your new stick figure is realistic and practical.

March 14, 2021 at 9:25 pm

That’s good to hear! In truth, the more simplistic (original) stick figure serves a different purpose – being a completely simplified rendition of the human figure that can be drawn in seconds – and in that regard, it is actually more efficient.

My goal with this post was to create a stick figure that more clearly represented the human body and it’s basic anatomy, one that is more useful as an immediate reference for drawing the figure.

May 24, 2024 at 8:18 pm

not good

January 15, 2025 at 10:42 am

play this game its good https://fightshadow2apk.com/

August 17, 2025 at 8:32 am

Matka king – final ank | satta matka | dpboss Matka |

October 27, 2025 at 3:53 am

No

October 9, 2024 at 3:15 pm

Argo Door & Window: Repair and Replacement, based at 21005 Watertown Rd, Unit D, Waukesha, WI 53186, is your premier destination for expert home window repair New Berlin, WI. With over eight years of experience, our skilled professionals handle everything from foggy glass to rotted wood, ensuring your windows are in optimal condition. We specialize in high-quality repairs for all American window brands, providing long-lasting solutions. Don’t hesitate to contact us at +12622397971 for a free estimate on your window repair needs. Visit our Waukesha location today to see how we can improve your home’s efficiency and appearance.

July 12, 2025 at 7:16 am

To me the stick figure image has always been a basic figure primarily made of sticks, (lines), and a circle. Your drawings are cool and all, however I wouldn’t consider them “stick” figures, more of a basic human shape figure, having the correct (ish) skeletol structure. Thank you for your ideas and theory.

August 17, 2025 at 8:33 am

Matka satta – indian matka 420 | dpboss matka | satta matka |

October 4, 2024 at 4:47 pm

At Home Window Repair & Replacement Service, we excel as a window repair Mooresville, NC, area, specializing in comprehensive repair solutions for window-related issues. Our team of professionals is adept at diagnosing and fixing problems ranging from simple wear and tear to more complex damage like broken mechanisms and rotted wood. We focus on extending the life of your windows and enhancing your home’s comfort and appearance. Each repair is performed with meticulous care and precision, tailored to fit your property’s unique style and needs. Contact us at 16507-A Northcross Dr, Huntersville, NC 28078, or call +19802383556 to discover how we can assist you.

December 20, 2025 at 7:18 pm

shut the fuck up

July 29, 2025 at 3:39 pm

Yes, I agree. VOS Doors & Windows in Illinois, is your reliable partner for all your window repair in Elmhurst, IL needs. Our team is equipped to handle everything from minor repairs to major renovations, ensuring that each window functions perfectly and enhances your home’s energy efficiency. Our extensive experience with all USA wood and vinyl window brands allows us to provide repairs that are both effective and durable. For expert window repair, call (630) 454-6690.

August 7, 2025 at 10:53 am

Interesting point! I agree — making figures more realistic definitely improves clarity and connection. Thanks for sharing! Also, if you’re in the UK and ever need to check if your car is insured, you can do it quickly at askMID Insurance.

March 15, 2021 at 2:53 am

Stick figures are great to get a starting figure for a drawing. They might just be seen as something children draw, but they really can be the base of a drawing. I think this is a great topic to talk about and it was nice to get a refresher on things even though I have been drawing for quite some time. When I first began drawing I always had a hard time drawing the torso. I did one of the common mistakes you mentioned by making the torso way too long. Overall, this is a great post and it will definitely help people who are getting into drawing.

March 15, 2021 at 3:45 pm

They’re a relatively ubiquitous starting point for drawing people, so I think it’s a good spot to start when it comes to understanding the human form.

Admittedly, this would have been a good post to start with, rather than dumping loads of information and terminology about anatomy on people, but I didn’t even think of this blog topic until I was halfway done writing my post about musculature. At the very least, I’ll be able to go back and reference previous posts about anatomy, if/when I start discussing it more in-depth.

March 16, 2021 at 9:50 pm

I remember drawing stick figures all the time, especially during classes in grade school. However, none were quite as defined or complex as what you’ve shown here. I agree, though, that stick figures can make an excellent base for more complex and detailed art.

March 17, 2021 at 8:02 pm

I used to draw stick figures non-stop as a kid, I drew tons of little comic books with stick figure characters. Honestly, even through high school, you could consider many of my drawings from that time to be elaborations on stick figures, since they lacked proper form(s) and anatomy.

March 9, 2022 at 3:19 am

Wertuo

Wertuo

October 14, 2023 at 4:58 am

I like it

October 14, 2023 at 4:58 am

Hdudjr

December 27, 2023 at 2:28 pm

Reading idea’s always great for the students and the learners, but bad thing is student not being going to research with specific thing and keep doing sad emoji typically.

January 26, 2024 at 4:41 pm

My Brother is used to play like this

March 22, 2024 at 6:11 pm

Appreciation for really being thoughtful and also for deciding on certain marvelous guides most people really want to be aware of.

April 2, 2024 at 9:18 pm

Helpful.. so W

April 8, 2024 at 12:12 pm

Browser and it is very nice.

fraud

April 16, 2024 at 6:00 pm

Great content.I really appreciate your effort.Thanks

bolly4u

April 19, 2024 at 8:57 am

How you can make dinner even more delicious and special? Homemade rolls! These delicious Copycat Texas Roadhouse Rolls are perfectly fluffy and amazing with any dinner!

https://wordpress.com/tr/forums/topic/wordpress-okey-oyun-temasi-2/

April 24, 2024 at 4:10 pm

this is a good site

May 7, 2024 at 11:55 am

Welcome to Yas Download’s online webpage. iPhone, iPad, iOS & Android video downloader with all features. You may download any video with this shortcut

May 20, 2024 at 1:25 pm

good

https://bolly4u.boats

June 8, 2024 at 5:01 am

Vozol Vista 20000 VZBull Redbull Enerji İçeceği

June 18, 2024 at 9:00 am

What an Article Sir! I am impressed with your content. I wish to be like you. After your article, I have installed Grammarly in my Chrome Browser and it is very nice.

short stories in hindi

July 14, 2024 at 10:58 am

This post is a wonderful resource that I’ll be referring back to again and again. Thank you! Yas Download is a powerful media downloading shortcut specially designed for iPhone or iPad users.

July 27, 2024 at 7:03 am

I am astonished by the level of contemplation and attention to detail you have dedicated to this. I value the motivation you provide me.

space waves game

August 12, 2024 at 2:21 am

Rare Toons IndiaAvails You all Animes, Cartoons, in Hindi – Tamil – Telugu dubbed Episodes in Multiple Quality like 1080p, .

August 13, 2024 at 3:38 pm

The new SASSA Scholarship Program is actually benificial for students worldwide especially students from South Africa

August 14, 2024 at 4:52 am

R Download is a magical shortcut designed specifically for iOS users. With it, you can effortlessly download photos, videos, and other media to your device’s gallery with just a single click.

August 20, 2024 at 12:21 pm

This article is incredibly insightful. Your thorough analysis and clear explanations really helped me understand the topic better. Thank you for sharing your expertise! Yas Download shortcut is an iOS tool that helps you download social media stuff.

August 21, 2024 at 11:55 am

Argo Glass & Windows is amid top-tier window replacement companies designed to enhance your home’s energy efficiency and comfort. Located in Arlington Heights, Illinois, our team excels in addressing and resolving issues related to old or damaged windows, such as drafts and condensation. We provide seamless replacements that fit perfectly with your home’s existing décor, using only the highest quality materials. Our commitment to excellence is supported by over eight years of experience in window replacement. For a free estimate or to schedule a consultation, please visit us at 317 W Colfax St, Palatine, IL 60067, or call +18476968044.

August 29, 2024 at 11:17 am

For reliable and efficient “best hvac service near me Elgin Illinois” choose Gold Shield Services, your local experts in Elgin. Our professionals are highly trained in the latest HVAC technologies and methods to ensure your system is in perfect condition. We offer comprehensive services that cover everything from initial diagnostics to complete system overhauls. With our focus on customer satisfaction and technical expertise, you can expect the best service and results. Visit our location at Gold Shield Services, 665 Tollgate Rd E, Elgin, IL 60123, or call +18474699934 to schedule your service today.

September 7, 2024 at 2:59 pm

In conclusion, improving stick figures by adding key details like the neck, clavicle, and pelvis can create a more realistic and expressive representation of the human form. By simplifying the structure without sacrificing anatomy, even basic drawings can be more effective. For those interested in sketching, it’s like leveling up your artistic skills, much like advancing in GTA 5 Spot.

September 13, 2024 at 2:59 pm

It was a really amazing guide. It helped me to overcome my fears and I am better than ever. Appreciate it. Please keep writing more such articles.

September 20, 2024 at 3:43 pm

good article

September 20, 2024 at 3:45 pm

Hi everyone

October 2, 2024 at 7:33 pm

.

October 2, 2024 at 7:35 pm

.

October 2, 2024 at 7:35 pm

The Delta Executor is a component in Databricks’ Delta Lake architecture that manages and coordinates the execution of transactions on Delta tables. It ensures atomicity, consistency, isolation, and durability (ACID) properties during write and read operations. By handling complex transaction logic, it optimizes performance and reliability for large-scale data operations.

October 5, 2024 at 3:39 pm

Be a part of an unprecedented and unlimited adventure with GTA San Andreas APK and enjoy the open-world gaming experience on your mobile device. Are you facing problems with the paid application? Then don’t worry about how to enjoy unlimited and smooth gameplay with this GTA San Andreas APK version without any interruption.

October 15, 2024 at 10:29 am

Stiker tetap diminati sampai sekarang, apalagi kita bisa desain sendiri bentuk stiker yang diinginkan

October 23, 2024 at 11:37 am

wep sayfanız gayet güzel tebrik ederim

October 28, 2024 at 7:10 am

I really appreciate the time and effort you put into making your content easy to understand. This post was well-written and very helpful.

If you have any iphone pleae visit this website dtiktok to download and connect this shortcut on your iphone. This shortcut will help you to download any reels from tiktok directly to your device gallery very easily.

November 5, 2024 at 3:34 pm

1. Excellent submit. I just stumbled your website dan love to analyzing your good web post. Will subscribe your website for any news coming. King338

November 5, 2024 at 3:35 pm

3. Thank you for completely thrilling web blog and written in perfectly fashion. Looking forward to read your new article. regards King338

November 5, 2024 at 3:35 pm

4. I read all recommendation published and this is good one and I get interesting information and can be useful to write new article. Regards King338

November 5, 2024 at 3:36 pm

6. Been read all your post. have to say, impressive work. keep doing good work King338

November 20, 2024 at 9:59 pm

“Learn how to improve your stick figure drawings with this comprehensive guide, and while you’re at it, check out [hilarious and creative goofy pictures](https://goofyahhpictures.us/) at GoofyAhhPictures.us to spark your artistic imagination!”

November 23, 2024 at 2:58 pm

LOVE YOUR STICK FIGUER BRO/G

DONT LET ANY ONE JUDGE YOU

December 9, 2024 at 7:30 pm

adding stick figures to the gaming guide website for Max the Elf is a great idea. Stick figures can simplify complex game mechanics and make the guide more approachable for players. They provide a clear visual representation of strategies and tips. Read more about the latest max the elf.

December 24, 2024 at 10:11 am

Excellent submit. Must Visit our website for stay goofy > https://goofyahhpictures.net/

January 6, 2025 at 9:03 am

great post

January 10, 2025 at 9:49 pm

great post https://loboflix.in/

January 19, 2025 at 11:14 am

I recently got the latest version of Summertime Saga game from sumsaga and installed it on my phone. The installation process was smooth, and I’m excited to start playing again. The new features and updates are always a great addition to the game, and I’m looking forward to exploring the new content.

January 23, 2025 at 11:52 am

i love Stick Figures

January 29, 2025 at 2:50 pm

FilmBus is an app that allows you to watch any movie web series at your leisure. It has a free and premium version.

February 1, 2025 at 4:26 am

Blox Fruits, scripts can help players unlock new strategies and improve their gameplay.

February 8, 2025 at 5:42 pm

One of the sensational gaming platform Bet PKR vip Game new APK v1.1.6 is an arena of the online gaming industry. Bet pkr Download will be the real and amazing game for real game players who knows to earn with slot games.

February 15, 2025 at 11:56 am

Thank you for providing such valuable information! I truly appreciate the effort you’ve put into sharing these insights. Your post is not only up-to-date but also highly informative. I’ll be bookmarking this page to revisit and explore more of your content in the future.

Keep up the excellent work! dramacool

February 16, 2025 at 9:58 am

thnks…

February 16, 2025 at 9:59 am

Thank you for posting our latest blog. Your support is greatly appreciated and helps us reach more readers. We’re grateful for your commitment to our blog and online community.

February 20, 2025 at 8:01 am

Dramacool | Watch Asian drama, Movies and Shows English Sub HD Without ads

February 21, 2025 at 9:47 am

Dramacool | Watch Asian drama, Movies and Shows English Sub HD Without ads

February 24, 2025 at 4:09 pm

Thank you for posting our latest blog. Your support is greatly appreciated and helps us reach more readers. We’re thankful for your helpful articles and we also wish that you will never stop of providing such informative articles.

March 16, 2025 at 4:54 am

i cant understand by the way………..

March 18, 2025 at 6:26 pm

Great artical thanks for sharing

March 18, 2025 at 6:27 pm

Informative blog post please keep sharing

March 18, 2025 at 6:28 pm

this artical very informative thanks for share

March 25, 2025 at 6:31 am

Thank you for sharing this great information, I loved it.

April 3, 2025 at 6:21 am

Watch, Read, and Explore with Dramanice Your Ultimate Drama Destination!

Enjoy the best Asian dramas with high-quality streaming and English subtitles.

Discover romance, action, and thrilling stories anytime, anywhere!

Drama Nice

April 8, 2025 at 8:29 am

Ennovelas is your exceptional objective for immersive portraying and captivating computerized books. Find a wide grow of sorts counting supposition, dramatization, meander off in daydream arrive, thriller, and more—updated each day with cutting edge scenes from gifted creators around the world.

April 13, 2025 at 5:22 am

Aloha Browser is a web browser that cares almost your security. It’s planned to keep you secure and secure online. To begin with, it has a solid advertisement blocker. https://alohabrowser.tools/

April 14, 2025 at 8:55 am

Absolutely agree—breaking down the human figure is no easy task, and it’s totally normal to feel overwhelmed at first. That’s why simplifying with stick figures is such a smart move—it gives you a solid foundation before diving into the complex stuff like bones and muscles. And hey, if you ever need a break or want to refresh your mind, check out Magis TV Fútbol —a free streaming app where you can watch live sports and more. It’s a great way to relax while still fueling your creativity. Give it a try at the official website!

May 5, 2025 at 4:41 am

Vanced YouTube is a modified version of the official YouTube app, developed by independent developers to add functionalities that are not available in the standard application. It is designed specifically for Android devices and offers a highly personalized and enhanced user experience.

May 5, 2025 at 8:18 am

For families castle app premium offers parental control features, allowing guardians to monitor and restrict content accessible to children.

May 6, 2025 at 5:25 am

Vidmate allows content download from hundreds of websites. Whether it’s a YouTube playlist or an Instagram reel, users can fetch the video with just a few taps.

May 9, 2025 at 3:35 pm

bilgilendirci yaralı bir wep sitesi

May 10, 2025 at 12:54 am

This blog series is interesting. stimulation clickerArticles are coherent with individual highlights. The systematic sharing is great. Looking forward to more great works.

May 10, 2025 at 12:59 am

So much valuable content!The languagecookie clicker style is relaxed and humorous, making it stress free to read

May 10, 2025 at 1:02 am

Great writing skills!It is not only easy to read but crazy cattle 3dalso makes the content more rich and interesting.

May 11, 2025 at 5:16 am

Great article thanks for sharing here.

May 13, 2025 at 1:55 pm

nice

May 13, 2025 at 2:36 pm

This is a pretty neat breakdown on improving stick figures! I never really thought about the anatomy in such a simple way. Makes me wonder if there’s a face symmetry test but for stick figures haha.

May 13, 2025 at 2:41 pm

This article is a great starting point for improving stick figures! Who knew there were so many ways to make them less…stiff? Haha. Makes me wonder if a Doll Generator could even help create better poses from the get-go!

May 13, 2025 at 3:05 pm

This is actually super helpful! I always draw terrible stick figures. Gonna try adding the clavicle thing, it seems easy enough. I wonder if they can make emojimyface ones 🤔 That would be so cool!

https://emojimyface.com

May 14, 2025 at 5:03 pm

This was very holpful thanks

May 14, 2025 at 5:04 pm

I like what you did with the second new improved stickman

May 15, 2025 at 4:20 am

My previous two posts (Studying the Skeleton, Studying Musculature) are quite lengthy, and may contain an overwhelming amount of information for some of you. Try as I may to keep things simple, drawing the human body is a complex process, with lots of moving parts.https://wosgroup.com/

May 15, 2025 at 9:16 pm

Best one so far, bookmarked and will read other articles again.

May 16, 2025 at 3:25 am

I like the stick figure drawings, they really helped me out how to draw people.

May 17, 2025 at 11:32 pm

Best one so far, bookmarked and will read other articles again. !

May 19, 2025 at 4:13 am

Amazing Article admin.

May 19, 2025 at 5:54 am

Good one, & best try.

May 21, 2025 at 6:08 pm

Thanks for the update! It’s always great to stay informed about what’s happening. Appreciate all the effort that goes into making these weeks run smoothly.

May 23, 2025 at 7:51 pm

Best one so far, bookmarked and will read other articles again.

May 27, 2025 at 9:08 am

TD777 Game Download is a newly launched online gaming application in Pakistan that allows users to play skill-based and chance-based games while earning real cash. Once the TD777 Game getting on smartphone, then you can easily play multiple games to get unlimited rewards.

May 28, 2025 at 4:18 pm

Very good article!

May 28, 2025 at 4:18 pm

Moni88 Situs Judi Bola, Parlay Online dan Slot88 Gacor paling gampang maxwin di Indonesia.

June 4, 2025 at 1:14 pm

Delta Executors Official provides a free, cross-platform Roblox script executor for Android, iOS, and Windows. It has a user-friendly interface and a built-in script library to enhance gameplay.

https://deltaexecutorsofficial.com/

June 5, 2025 at 2:04 pm

Good post, thank you.

regardersoustitre facebook page

June 5, 2025 at 2:14 pm

Nice article, thank you.

guardasottotitoli facebook page

June 5, 2025 at 2:29 pm

Good post, thank you bro.

versubtitulos facebook page

June 6, 2025 at 2:31 am

Good post, thank you.

ULTRA HD facebook page

June 6, 2025 at 2:53 am

Good post, thank you bro.

MOVIE HD facebook page

June 9, 2025 at 11:40 am

Good post, thank you bro.

Seriedfilm Subtitulo facebook page

June 9, 2025 at 11:49 am

Good article, thank you bro.

Seriedfilm Subtitulo facebook page photos

June 9, 2025 at 12:52 pm

Good post, thank you admin. Rize is known for its lush green landscapes, tea plantations, and scenic mountains, making it a popular destination for nature lovers and adventure travelers.

June 12, 2025 at 9:50 pm

Recomiendo totalmente Becas Ritacetinas, encontré info súper clara y útil sobre becas.

June 14, 2025 at 4:37 am

Parivahan is one of India’s best government digital services, offering convenient, transparent, and efficient access to transport-related services. It allows users to apply for driving licenses, register vehicles, pay road tax, and check challans online—eliminating long queues at RTOs. Integrated across states, it ensures uniform services and easy tracking of applications. With tools like the mParivahan app, it supports paperless governance and the Digital India initiative. https://sewaparivahan.com/

June 14, 2025 at 11:29 am

Situs Slot Olimpus 1000 Maxwin Super Scatter Terbaru 2025

June 16, 2025 at 10:23 am

GTA 6 APK is an action-packed and adventure mobile game played all over the world. It is known due to its thrilling open world adventures, the Grand Theft Auto Series, which allows players to explore massive cities, drive a wide range of vehicles, complete action-packed missions, and engage in different exciting activities.

June 17, 2025 at 6:11 am

What a great post by you. I love it.

June 20, 2025 at 6:40 am

Without that midline, those parts would just be floating in space, attached to nothing…

June 24, 2025 at 7:14 am

This is actually super helpful! I always struggled with making my stick figures look less…stiff.

June 24, 2025 at 3:48 pm

app, it supports paperless governance and the Digital India initiative. Sso ID is a part of it

June 24, 2025 at 3:49 pm

SSO ID

is a transport and logistics management system designed to streamline vehicle tracking, fleet management, and cargo transportation. It utilizes GPS technology and real-time data to enhance route planning, reduce delays, and improve operational efficiency. Prevahan is especially useful for businesses seeking greater control over their supply chain and transport operations. It helps monitor driver behavior, optimize fuel usage, and ensure compliance with regulatory requirements. This system plays a vital role in making transportation more transparent, accountable, and cost-effective.

like this write a comment so i can post to manuplate google and get ranking

June 25, 2025 at 4:09 pm

Good post, thank you.

Les Film Serie FR facebook page

June 25, 2025 at 4:16 pm

Good article, thank you.

Serie di Film ITA facebook page

June 25, 2025 at 4:22 pm

Good job, thank you.

Series de Película facebook page

June 25, 2025 at 4:29 pm

Good post, thank you bro.

Watch Streaming Seriedfilm facebook page

June 29, 2025 at 4:37 am

Download apk singa8 Mahjong Scatter Hitam Slot Bet Kecil 40 Rupiah Terbaru Indonesia

June 30, 2025 at 6:50 pm

sassa status check for r350 payment dates

Great tips for keeping your SASSA details up to date to avoid any delays in receiving payments.

Make sure to regularly verify your information and stay informed about the latest updates.

July 1, 2025 at 6:43 am

In conclusion, adding simple details like the neck, clavicle, and pelvis can really bring stick figures to life, making them more realistic and expressive. It’s all about keeping things simple while still capturing the basics of human anatomy. If you enjoy sketching, think of it as leveling up your art skills—kind of like progressing in avatar world geeks!

July 5, 2025 at 7:35 am

Do you want to buy unicorn pyjamas ? You can buy them at Maison de la Licorne

July 5, 2025 at 10:04 pm

Appreciate the clear timeline—this is exactly the info aspiring officers need to organize their application process

July 5, 2025 at 10:41 pm

Breaking complex anatomy into simple lines is genius—now I actually understand proportion before diving into details

July 12, 2025 at 10:07 am

Thank you for sharing valuable information. Provided information is upto date & well-structured. I’ve book marked this website for future updates.

July 13, 2025 at 2:55 pm

Thanks for sharing! Enjoy relaxing with the New York Times Connections game. For expert solutions and past puzzles, explore our professional Connections Archive at [Connections Hint Today Answers], the top destination for puzzle fans!

July 14, 2025 at 6:15 am

https://parivahansewa.co/ is India’s digital transport portal by Ministry of Road Transport and Highways, offering online services for driving licenses, vehicle registration, permits, and traffic challans across all states.

July 14, 2025 at 6:18 am

sewa parivahan streamlines India’s transport services through VAHAN and SARATHI systems, enabling citizens to access driving license applications, vehicle registrations, renewals, and eChallan payments online nationwide.

July 15, 2025 at 1:21 am

Hey there! I think it’s so cool that you’re diving into the nitty-gritty of stick figures. It really makes a difference in making them more lifelike, huh? When I was learning to draw, I struggled with proportions too, but focusing on simple shapes like you suggested really helped. By the way, if you’re interested in picking out some fun stationery for your art projects, I found this great resource on trendy stationery that you might like! great resource on trendy stationery

July 15, 2025 at 1:22 am

Wow, this post is super enlightening! I never realized how each body part connects. It’s amazing how simplifying complex shapes can make the stick figures more relatable. When I was getting into art, having a reliable color chart really helped in choosing the right colors. Speaking of colors, I found a comprehensive Pantone Colors Chart that you might find handy for your drawings! comprehensive Pantone Colors Chart

July 15, 2025 at 1:22 am

Oh, I love how you break down the drawing basics! It’s so refreshing to see someone address common mistakes instead of just glossing over them. I remember feeling so lost with details and proportions, but focusing on the essentials transformed my approach completely. Also, for anyone experimenting, I came across this AI color changer that makes it a breeze to tweak your art. You might find it useful! AI color changer that makes it a breeze to tweak your art

July 15, 2025 at 7:08 am

Welcome for this useful information, I have bookmarked and written some things down. I will be checking back, from time to time too.

July 15, 2025 at 1:30 pm

SINGA8 Apk Slot Olympus 1000 Super Scatter Terbaru Bet 40 Terpercaya Di Indonesia

July 15, 2025 at 3:06 pm

“This downloader is a game changer for TikTok fans like me!”

SSSTikTok

July 16, 2025 at 3:43 pm

I really enjoyed your breakdown of stick figure anatomy—it’s a great starting point for beginners like me. After practicing my drawings, I like to unwind with some fun games at sansfight.io. It’s cool how art and gaming both let us explore creativity in different ways!

July 17, 2025 at 9:24 am

It’s amazing how shared stories create such connection

July 17, 2025 at 9:26 am

Your efforts are truly appreciated. You have made a real difference in the lives of many

July 21, 2025 at 1:19 pm

Nice post, thank you.

Film Sub ita on X

July 21, 2025 at 2:30 pm

Nice article, thank you.

imovieseries

July 22, 2025 at 11:19 am

Your website is very nice, a fluent article, congratulations

July 24, 2025 at 12:28 pm

FESCO Bill is a convenient online service that lets Faisalabad Electric Supply Company customers quickly check, download, and print their electricity bills. Simply enter your 14-digit reference number on FESCOBilling.pk

to access your latest bill anytime, from anywhere

July 25, 2025 at 8:13 am

Trusted online slots that are ready to give you big jackpots that you can play on the site https://personate.id/

July 26, 2025 at 6:54 am

Great content.I really appreciate your effort.Thanks

https://hdphotoconverter.org/

July 26, 2025 at 8:08 am

Great post! I really enjoyed reading this.

July 27, 2025 at 1:42 pm

The Parivahan Sewa portal, which we briefly evaluate in this blog, has made it possible to complete certification and processes for services related to vehicles and licenses digitally.

July 27, 2025 at 3:57 pm

Gold rates for 24-carat gold in Qatar are influenced by global market conditions and local demand. As the purest form of gold, 24K is highly valued for investment and jewelry. The price tends to fluctuate based on factors like economic conditions, geopolitical events, and the overall demand for precious metals. For more details, check the gold rate in Qatar today 24 carat.

July 28, 2025 at 9:08 am

Platform topcer88 bisa jadi alternatif hiburan digital yang menarik saat ini.

July 29, 2025 at 4:16 am

That is funny, l like it

July 29, 2025 at 4:18 am

Thanks for sharing, very interesting

July 31, 2025 at 2:40 pm

Use Grow a Garden Value Calculator for Roblox’s. Instantly calculate crop values and optimize your strategy.

August 1, 2025 at 1:38 pm

The latest version of Vidmate Apk is amazing. It’s more stable, faster, and even cleaner in terms of design. The integrated search bar makes it easier to find videos directly within the app, and the new dark mode is a nice touch.

August 2, 2025 at 8:18 am

Unlike many platforms, meme sound buttons doesn’t ask you to register or install anything. The entire experience from browsing and searching to playing and sharing is browser-based and fully open. Whether you’re a creator, gamer, or casual meme lover, it works instantly across all your devices.

August 2, 2025 at 10:06 am

The askMID service allows you to confirm if your vehicle is currently showing as insured on the Motor Insurance Database.

August 2, 2025 at 10:06 am

GST stands for Goods and Service Tax and it was introduced to avoid the cascading tax effect that means charging tax on tax. On the other hand, the government has made it easy for individuals to manage their GST online through the GST Login Portal.

August 2, 2025 at 10:07 am

nbm Application Status & Payment Status Check: Andhra Pradesh government has launched NBM GSWS portal at gsws-nbm.ap.gov.in where you can check your NBM application status or payment status for different welfare scheme for the year 2025-26.

August 2, 2025 at 10:08 am

The Employees’ Provident Fund Organisation EPFO is one of the largest social security organisations in India, established under the Employees’ Provident Funds and Miscellaneous Provisions Act, 1952..

August 6, 2025 at 5:11 am

The Privahan Sewa offers a variety of services, including online services, Sarathi Parivahan driving license services, Vahan parivahan vehicle registration permits, Check post tax payments, RTO registration, learner’s license services throughout India.

August 6, 2025 at 7:22 pm

Joining Boys WhatsApp Groups has become very easy with this website.

August 7, 2025 at 1:44 pm

This post is so helpful! It’s true, drawing people is hard, even stick figures can be tricky. Sometimes I wish I had a Photo Prompt to help me get started with poses. It would make things so much easier!

August 8, 2025 at 11:24 am

“Interesting breakdown! I never realized how small tweaks like joint positioning can make stick figures feel more dynamic. It kind of reminds me how in video games, especially in something like Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2, small tweaks (like aim assist settings or trainer tools) can totally change the way a character moves or reacts. I’ve been diving into that lately fun how both drawing and gaming rely on little adjustments to feel more ‘real.’ Thanks for the tips!”

August 8, 2025 at 12:52 pm

This was actually a really helpful post. I’ve always struggled with getting proportions right when drawing stick figures, especially when trying to use them for planning character movement. I recently started exploring animation mods and character trainers in games like

WWE 2K20. where understanding basic poses and movement flow really makes a difference. Posts like this help bridge the gap between basic drawing and more advanced game design ideas.

August 9, 2025 at 9:03 am

Gamified content keeps Gen Z engaged by blending entertainment with interaction, turning passive consumption into active participation. Features like challenges, quizzes, leaderboards, and rewards tap into their competitive nature and desire for instant feedback. By integrating elements of play into learning, shopping, or social media experiences of Z Engaged, brands and creators capture Gen Z’s short attention span while making the content feel more personal and immersive.

August 9, 2025 at 8:15 pm

If you want to play tough and want to hate this I’ll always show up and make a statement. Everything I do so instinctive and so passionate.

August 11, 2025 at 10:26 am

You are not alone if you are battling inconsistent streaming services or bored of paying for costly cable subscriptions. Many individuals are searching for a fundamental, free way to view live TV from the convenience of their house.

August 11, 2025 at 12:47 pm

The Money Wave Official Website — this guided audio session gently reprograms your subconscious mind to attract wealth naturally and effortlessly.

August 13, 2025 at 10:06 am

“I’ve been testing out script tools for Roblox, and Delta Executor stands out—its clean interface, speedy script injection, and regular updates really impressed me. If you’re into Lua scripting or want reliable custom features, check it out at DeltaExecutors.app!”

delta executors/

August 13, 2025 at 6:38 pm

It’s a favorite among players seeking extra advantages, downloading and usingredz hub blade ball is against Roblox’s terms of service and may result in account warnings or permanent bans.

August 14, 2025 at 12:11 pm

Stick figures are such a simple yet powerful way to break down human anatomy when starting out. They help with proportion and pose before adding any detail, which is why even pros sometimes sketch them first. I use the same approach in other hobbies too — starting simple and building up.

August 14, 2025 at 5:51 pm

Maximize your chances of winning with exclusive strategies that you can apply and take advantage of your luck in online betting. https://theglobaltake.com

August 18, 2025 at 12:33 pm

This article is really informative and well-written. Looking forward to reading more of your valuable posts.

August 18, 2025 at 1:31 pm

Parivahan Sewa

has made transport-related services extremely easy and accessible. Now you can avail driving license application, renewal, obtaining duplicate license, and many other services from the comfort of your home. The portal offers time-saving, transparency, and convenience, which is a major achievement in today’s digital era.

August 19, 2025 at 9:12 am

The Boys WhatsApp Group Links are very popular these days worldwide for fun and entertainment chat.

August 23, 2025 at 3:03 pm

Great tips on drawing stick figures! It reminds me of how step-by-step guides can make things easier, like the video walkthroughs at playcolorblockjam for mastering game levels.

August 24, 2025 at 11:42 pm

You nailed the basics here, but don’t forget those little details like hands and feet, they matter! Check Sprunki out for a fun way to add some flair to your character design

August 26, 2025 at 9:55 am

Snow Rider 3D is an addictive snow racing game where you guide your sled through endless snowy hills.

August 27, 2025 at 6:00 am

Thank you for providing useful and very good information.

August 28, 2025 at 12:31 am

Great breakdown of stick figure fundamentals! Adding the clavicle and pelvis lines really helped me see how to improve my poses without overcomplicating things. Your explanation of fixing common mistakes made the process of drawing stick figures much clearer and more approachable.

August 28, 2025 at 12:40 am

Great breakdown of stick figure basics! I especially appreciate how you highlight the importance of the clavicle and pelvis lines to improve realism without complicating the drawing. This approach really helped me refine my foundational sketches when practicing figure drawing.

August 28, 2025 at 9:40 am

Supermaker GOOD article,It is so useful for me

August 31, 2025 at 10:38 am

https://www.youdao4.com

September 1, 2025 at 6:49 am

Halo, Anda telah melakukan pekerjaan yang fantastis. Saya pasti akan menggalinya dan secara pribadi merekomendasikan kepada teman-teman saya. Saya yakin mereka akan mendapat manfaat dari situs ini.

September 2, 2025 at 4:23 pm

The Government of India has started the e-Shram Card scheme for unorganized workers. You can download the e-Shram Card registration from the e-Shram Card portal.

September 2, 2025 at 4:26 pm

Rajasthan government has started SSO ID for all the teachers and students of the state

September 2, 2025 at 9:48 pm

Amazing

September 5, 2025 at 3:14 pm

This is a helpful tutorial! I always struggled with making my stick figures look right. The tips about the shoulders and dividing the arms/legs are really useful. I’m definitely going to try these out. Anatomy and how to represent it in a simple form is key!

September 6, 2025 at 7:14 pm

Why don’t you join the Latest WhatsApp Groups

September 8, 2025 at 4:45 pm

Information related to MP Bhulekh land map has been made available online by the Madhya Pradesh government on the MP Bhulekh portal

September 10, 2025 at 2:55 am

This post nails the basics on drawing stick figures, but it could use some examples to really drive the points home. Oh, and if you’re into music, check out this Sprunki juego for some creative inspiration.

September 12, 2025 at 4:46 am

Thoughts on “How to Draw: Fixing the Common Flaws with Stick Figures”

This is a friendly, practical guide — perfect for beginners who want to build confidence before moving on to more complex figures. I like how the post breaks down posture, proportion, and gesture into simple steps that actually feel doable. Practicing those small adjustments makes a big difference in bringing stick figures to life.

If you’re using exercises like these in a school or workshop setting, remember to check the consent and data policies for students involved in any published work or portfolios. A useful reference is the parental consent checklist, which explains the permissions schools should gather when handling student records or sharing student-created content.

Overall, great tutorial — simple, clear, and very encouraging for anyone starting to draw.

September 13, 2025 at 8:30 am

I really liked how you explained fixing common flaws with stick figures, it makes drawing much easier for beginners. For more helpful resources, check out this useful site.

September 13, 2025 at 10:55 am

Simply add your Avatar image and audio, and prompt the emotions and expressions to bring your Avatar to life! Kling AI Avatar

September 13, 2025 at 10:56 am

Nano Banana Image Generator: Redefining AI Image Generation,Experience advanced context-aware image generation and editing. Input text, images, or both to create coherent, high-quality visuals tailored to your needs.

September 15, 2025 at 10:14 am

수원출장안마는 고객 편의를 위해 간편한 예약 시스템을 운영합니다. 원하는 시간과 장소에 맞춰 전문 마사지사가 방문해 체계적인 맞춤 마사지를 진행합니다. 수원출장안마

September 16, 2025 at 12:58 am

Such a clever and helpful guide! Love how it makes drawing accessible by fixing simple stick figure flaws. Really fun approach for beginners!

September 16, 2025 at 2:25 am

Enter Nano banana AI built on Google’s cutting-edge AI models This free, intuitive platform empowers you to generate and edit visuals with simple text prompts, making creativity accessible to everyone.

September 17, 2025 at 3:28 pm

Aš labai rekomenduoju MidjourneysRef.com/ko visiems, kurie naudoja MidJourney.

Čia rasite didelę SREF kodų kolekciją su pilnais promptais, paveikslėlių ir vaizdo įrašų pavyzdžiais.

Stiliai suskirstyti į kategorijas (anime, cyberpunk, retro, surreal ir kt.), todėl labai lengva rasti įkvėpimą.

Svetainė nuolat atnaujinama ir rodo populiariausius kodus – patogu tiek pradedantiesiems, tiek pažengusiems kūrėjams!

September 18, 2025 at 1:36 am

Those anatomy posts are deep, so tackling stick figure flaws sounds like a great way to simplify. Speaking of tools, for game dev, you sometimes need to reach out to people. A good Email Extractor can really help streamline finding contacts.

September 18, 2025 at 8:57 am

lsix game is the best place for online players. Come to the official site today and have a look around games, entertain yourself, and begin making real money immediately and in a secure manner.

September 18, 2025 at 9:03 am

I simply love online game platforms, and 1jj game appears to be a great choice. Users can make real money and enjoy a seamless experience by accessing the official website.

September 18, 2025 at 2:23 pm

9P99 game official website is a wonderful destination for those interested in playing thrilling games. It provides entertainment, trustworthiness, and genuine earning possibilities for serious gamblers.

September 18, 2025 at 2:25 pm

If you are on the lookout for an actual money gaming site, seven game is a place to go. The official website gives the users a secure, thrilling, and rewarding experience every single day.

September 21, 2025 at 4:28 pm

Greate!

Welcome to Grow a Garden.ers are hooked!

September 19, 2025 at 3:50 pm

Hi to everyone

September 21, 2025 at 4:23 pm

The shrug emoji ¯\_(ツ)_/¯ (also known as the shrug emoticon or shrug text) is a quick way to express uncertainty, indifference, or “I don’t know.”

September 21, 2025 at 4:23 pm

Play the classic Google Color Tiles and discover more colorful puzzle games. Match colors, eliminate tiles, and challenge yourself with endless fun!

September 21, 2025 at 4:24 pm

Hot Pre-Sale! Tap to draw your Nano Banana Prompt and unlock random pets, crops, and more surprises!

September 21, 2025 at 4:30 pm

There’s a certain grace in the way you approach everything FLUX.1 Kontext.

September 21, 2025 at 4:40 pm

wow! An animated musical fantasy where K-pop meets supernatural adventure.

KPop Demon Hunters Coloring Pages

September 21, 2025 at 4:41 pm

Aadhaar is a 12-digit unique identification number issued to residents of India by the UIDAI. It is based on an individual’s biometric and demographic data and serves as a proof of identity and address.

September 22, 2025 at 5:58 am

Enter Coloring page text on ColorArt Ai Coloring Page generator will be the best Choice for educatonal and Amz KDP Seller.

September 24, 2025 at 1:42 pm

Get personalized help from a MATLAB expert

who understands academic and technical requirements. Whether it’s simulations or debugging, expert solutions make your work easier.

September 25, 2025 at 2:01 am

This was such a helpful breakdown! I never realized how many common mistakes we make with simple stick figures—like starting the arms at the neck or skipping the pelvis. The step-by-step improvements with clavicle, pelvis, and masses really make the figure look more realistic while still keeping it simple. Definitely makes me feel more confident about my doodles!

October 2, 2025 at 6:40 am

This breakdown makes stick figures so much clearer and more practical! I love how you kept it simple while still fixing the biggest mistakes. Adding shapes for mass really takes them to the next level.

September 26, 2025 at 2:54 am

VEOE AI Create stunning videos with audio using Google’s most advanced Veo 3 AI model.

September 26, 2025 at 7:12 pm

Join today and enjoy premium online betting services designed just for you. Register now and join thousands of players who have experienced the thrill of online betting on this site https://hflrzzl.com

September 27, 2025 at 6:40 am

This is exactly what I needed! Your previous posts on anatomy were a bit overwhelming, so I appreciate you breaking things down. Focusing on fixing common flaws with stick figures sounds like a much more manageable starting point for a complex topic. Thanks for sharing this!

September 28, 2025 at 2:46 pm

nice

https://tweetlen.com

October 1, 2025 at 2:17 pm

Really enjoyed this article! 🎨 The tips on correcting common flaws in stick figures are clear and helpful. The advice about proportion and gesture lines especially resonated with me — it’s amazing how small adjustments can make a big difference.

One question: when you recommend refining the joints (elbows, knees) to make them less angular, do you have a trick for maintaining fluidity in movement, especially in dynamic poses?

Thanks for sharing such practical drawing guidance — it’s truly useful for artists at all levels!

October 3, 2025 at 6:55 am

The breakdown of common stick figure mistakes was both practical and easy to follow. Your points on proportions and using gesture lines stood out to me — it’s surprising how even subtle tweaks can completely change the energy of a drawing.

I found this piece really insightful! ✏️ I do have a curiosity though: when you suggest softening the joints like elbows and knees so they don’t appear overly sharp, is there a particular method you use to keep the sense of motion smooth, especially in action-heavy poses?

Appreciate you putting together such actionable tips — they feel relevant for beginners and experienced artists alike

October 3, 2025 at 3:45 pm

Great insights! I’ve been using Nano Banana AI for natural language image editing. Just describe what you want in plain English and it delivers professional results in seconds. Perfect for content creators!

October 6, 2025 at 7:36 pm

If you’re hunting for a place to unwind and play, go here to explore H555 Game — simple to use and full of fun!

October 8, 2025 at 4:56 am

Download the delta app from our facebook group page now

October 8, 2025 at 10:21 pm

Your blog is a goldmine of valuable insights.

October 10, 2025 at 2:03 am

>>>BARCELONA88<<< REKOMENDASI BO NOMOR 1 DI INDONESIA

October 10, 2025 at 11:01 am

Thanks for sharing our latest blog! Your support means the world to us and helps us connect with more readers. We’re truly grateful for your insightful articles and hope you continue creating such valuable content. Keep inspiring and informing others!

October 10, 2025 at 11:41 pm

Great tutorial, your tips on proportion and posture really clear up the common mistakes many beginners make.

I especially liked how you break down the steps into simple, manageable adjustments.

For readers looking into community outreach, public health, or nutrition work in local settings, you might find this resource interesting:

Aahar Jharkhand.

Thanks for sharing your knowledge and making drawing more accessible!

October 11, 2025 at 7:52 am

Wow, this is super helpful! I always struggle with making stick figures look dynamic. Speaking of cool visuals, have you seen Ghostface AI? It turns photos into awesome 90s horror scenes. Might be fun to use those silhouettes for figure practice, too!

October 11, 2025 at 7:52 am

This is super helpful! I always struggle with making stick figures look less stiff. Speaking of professional looks, have you tried Headshot AI? It’s a great way to get a polished headshot without the studio hassle, perfect for LinkedIn or your portfolio!

October 11, 2025 at 7:52 am

This is a great breakdown! Simplifying anatomy is key for beginners. Sometimes I sketch really small and then need to blow it up. I bet an Image Upscaler would be super helpful to clean up those initial rough sketches and make the lines crisp!

October 11, 2025 at 8:36 am

Go to our website for more information about delta executor

October 13, 2025 at 3:34 am

https://sora-video.org/

October 13, 2025 at 3:38 am

https://123d.app/

October 13, 2025 at 3:41 am

https://www.applebanana.org/

October 13, 2025 at 3:56 am

https://imgart.app/

October 13, 2025 at 3:57 am

https://ai3d.cc/

October 13, 2025 at 4:04 am

https://grokimage.org/

October 13, 2025 at 4:06 am

https://www.grokvideo.app/

October 13, 2025 at 4:20 am

https://www.grokimagine.one/

October 13, 2025 at 11:03 am

Parivahan is one of India’s best government digital services, offering convenient, transparent, and efficient access to transport-related services. It allows users to apply for driving licenses, register vehicles, pay road tax, and check challans online—eliminating long queues at RTOs. Integrated across states, it ensures uniform services and easy tracking of applications. With tools like the mParivahan app, it supports paperless governance and the Digital India initiative. https://parivahansewa.uno/

October 16, 2025 at 1:32 am

This post is so helpful! Drawing the human body is definitely tricky, even for stick figures. I bet an AI could help with some of those tricky poses. Have you tried using something like banana ai for inspiration?

October 16, 2025 at 3:20 am

This sounds great! I definitely felt a bit overwhelmed by the last two posts, so a simpler approach to anatomy is much appreciated. Even with stick figures, getting the angles right for limbs can make a huge difference. Sometimes I wish I had an online protractor tool to help with those tricky bends!

October 17, 2025 at 6:42 am

This sounds great! Your previous posts were super insightful, but yeah, anatomy can be a lot. Fixing stick figures is a perfect way to ease into things, especially for game development. Speaking of games, I’ve been really enjoying `pipsnyt` lately – it’s a surprisingly fun little title!!!

October 18, 2025 at 10:36 am

FM WhatsApp is a modified version of the original WhatsApp, created by Fouad Mokdad, that offers advanced privacy options and full customization features. Unlike the official app, FM WhatsApp lets you hide your online status, blue ticks, typing indicator, and even prevent others from deleting messages. It also allows you to apply custom themes, change fonts and icons, and lock specific chats without using a third-party app. Since it’s not on the Play Store, download FM WhatsApp from https://fmwhsapp.com/ to get the latest safe version.

October 19, 2025 at 9:24 am

Funny sticker figure

https://chatgptimage.art

October 20, 2025 at 12:47 pm

I found this post very easy to follow, it clarified some points I wasn’t fully sure about. Recently I’ve also been trying out this tool and it’s been quite helpful: Lipsync AI.

October 20, 2025 at 12:47 pm

This article really helped me understand the basics, appreciate it a lot! By the way, I found this tool very useful: Flux.2 AI.

October 20, 2025 at 12:48 pm

The way everything is laid out here makes it so much easier to understand. I’ve been exploring different resources and found this tool especially practical: ImagetoVideo.

October 21, 2025 at 2:31 pm

Amazing! AI Undress

October 21, 2025 at 4:06 pm

That’s great! Aurealisa stick figure drawings have always been stiff. Focusing on the action line ($Action Line$) really opens up new perspectives. Thanks for sharing this simple yet impactful trick! Give it a try!

October 22, 2025 at 12:10 am

Thank you for this wonderfully accessible approach to drawing fundamentals! As someone who often feels intimidated by complex anatomy tutorials, your focus on stick figures feels like a breath of fresh air. I particularly appreciate how you frame them as a universal visual framework – it’s so true that even professional artists start with these basic structures. Your teaching style makes daunting concepts feel approachable, and the personal touch about your mom’s comment added genuine warmth. Looking forward to applying these insights to my own beginner sketches!

October 22, 2025 at 6:10 am

https://remover.video

October 23, 2025 at 9:02 am

This sounds super helpful! I totally get how daunting anatomy can be. Starting with stick figures for game development is smart. Mastering these basics would be crucial for designing realistic characters, maybe even for a cool purble place online game!!

October 23, 2025 at 9:02 am

This sounds super helpful! I totally get how daunting anatomy can be. Starting with stick figures for game development is smart. Mastering these basics would be crucial for designing realistic characters, maybe even for a cool purble place online game!!!

October 26, 2025 at 7:31 am

best chose Parivahan Sewa

October 26, 2025 at 5:29 pm

This is such a helpful post! Drawing stick figures seems simple, but getting the proportions and balance right can be tricky. Your tips make the process so much easier — thanks for sharing! 🙌

I recently worked on a small creative project where I had to use basic illustrations. If anyone’s interested, you can check it out here</a

October 27, 2025 at 7:53 am

That’s cool! I’ve always loved drawing stick figures, but they always looked a bit weird. These basic anatomy tips are really helpful for improving the drawings. And speaking of fun, has anyone heard of TinyFun?

October 29, 2025 at 10:27 am

This post is a refreshing reminder that even the most complex artistic skills begin with mastering the basics. Stick figures, often overlooked, are actually powerful tools for understanding proportion, gesture, and movement before diving into full anatomy. By learning to fix common stick figure flaws—like stiff poses or uneven proportions—you build the foundation for more dynamic and realistic drawings. For those who want to unwind after sketching sessions, you might also enjoy exploring some visual storytelling through films on desicinemas.app, a free streaming platform where you can watch a wide range of content for inspiration and relaxation.

October 29, 2025 at 10:56 pm

Buy Maplestory mesos Farming Service Cheap and quickly accumulate mesos without the hassle of long grinding sessions. Trusted services offer budget-friendly options, so you can focus on your gameplay while experts handle the resource gathering.

October 31, 2025 at 4:18 am

BASEBALL 9 is an exciting, realistic sports game about baseball. Become the manager of a professional baseball team and lead your team to victory, competing in higher-level tournaments.

October 31, 2025 at 12:52 pm

I’ve heard a lot about ,blookket hacks lately — some say they make the game easier, but I think playing fair keeps it way more fun and challenging! 🎮

November 1, 2025 at 5:37 pm

I’ve always loved games that make you feel the thrill of speed and balance, and seeing how movement is analyzed in drawing tutorials gives a similar sense of focus. For an exciting 3D experience, Snow Rider 3D is a perfect choice to test your reflexes.

November 1, 2025 at 5:37 pm

Simple concepts can be surprisingly addictive when done right, like in puzzles or strategy exercises. The same principle applies to the logic in stick figure drawing. For a sweet and fun brain teaser, try 2048 Cupcakes—it’s both cute and challenging!

November 1, 2025 at 5:38 pm

Learning proper proportions and structure in figure drawing really makes you appreciate attention to detail and strategy. Games that require careful thought feel similarly rewarding. Speaking of strategy, Wordle infinite is an excellent way to challenge your mind with words.

November 2, 2025 at 6:03 am

This is a really helpful reminder that even simple stick figures can be improved with a few tweaks. I remember when I started drawing, my stick figures were so stiff! Focusing on proportions and posing really does make a difference. Thanks for breaking it down!

November 3, 2025 at 6:25 am

The new Gigi Brawler joins Null’s Brawl with elegant moves and powerful attacks. Unlock her instantly and explore exclusive content in the latest server update.

November 5, 2025 at 3:45 am

This post does a great job of reminding us that even the most complex skills, like drawing the human body, start with simple foundations — and stick figures are the perfect place to begin. By breaking things down to their core, the author makes anatomy and movement easier to grasp, even for beginners. If you’re looking for more creative learning breaks or inspiration beyond art, you can check out Dooflix, a free streaming app (iOS version available) that offers a wide range of educational and entertaining content to enjoy while you practice your drawing basics.

November 5, 2025 at 4:59 am

Thanks for this! It’s great you’re addressing the overwhelm from previous posts. I appreciate the focus on simplifying complex anatomy by starting with stick figures. That sounds like a much more approachable way to tackle drawing the human body, especially after all those detailed studies!!

November 6, 2025 at 4:47 am

Seva Sindhu portal launched in 2017 by the Government of Karnataka, is a digital platform that provides easy access to over 880 government services. It aims to simplify administrative processes, reduce the need for physical office visits, and offer a user-friendly interface for various services like applying for certificates and enrolling in welfare schemes.

November 6, 2025 at 6:14 am

IPL 2026 ka Ticket booking will be live soon on this website

November 6, 2025 at 6:15 am

IPL 2026 ka Ticket booking will be live soon on this website

November 10, 2025 at 1:18 pm

HiAnime allows you to stream thousands of anime shows and movies online.

Enjoy HD quality, fast servers, and easy navigation across genres.

No account needed, just open and start watching instantly.

November 12, 2025 at 8:23 am

Great post! I totally agree that stick figures are a fantastic starting point. I used to dismiss them, but now I use them to quickly block out poses before adding detail. It’s a great way to focus on gesture and composition first. Looking forward to the tips on making them more realistic!

November 12, 2025 at 11:47 am

At Credveda, borrowers enjoy the advantage of a low interest rate across all loan categories — personal, home, or business. This ensures affordable EMIs and long-term savings. Transparent pricing and fair policies make Credveda a trustworthy choice for anyone seeking cost-effective financial help.

November 12, 2025 at 6:45 pm

Bhoomi is a flagship e-governance initiative by the Government of Karnataka, launched in the year 2000, to digitize and provide online access to the state’s land records.

November 13, 2025 at 8:19 pm

Parivahan Sewa connects you to essential vehicle services in India. Check application status and manage your vehicle online.

November 14, 2025 at 5:44 am

https://rr88.navy/ là nền tảng trực tuyến cung cấp dịch vụ giải trí kỹ thuật số, hướng đến trải nghiệm tiện ích, tốc độ và bảo mật cho người dùng trên toàn cầu.

November 16, 2025 at 6:16 am

IPL ka Ticket Price will increase after changing GST from 28% to 40%

November 16, 2025 at 12:33 pm

Great tips! I like how you break down the common mistakes in drawing stick figures and show simple ways to fix them — it makes the process feel much more approachable. In the same way, Parivahan Sewa simplifies complex vehicle-related tasks for users, making things easier and more accessible just like your drawing guidance.

November 17, 2025 at 9:29 am

heelo?

November 17, 2025 at 9:30 am

https://intent.app

November 17, 2025 at 9:31 am

https://intent.app

Intent is an AI-driven cross-language messaging app with real-time translation, AI voice cloning, speech-to-text transcription, writing suggestions, and tone guidance—so you can truly connect using your own language.

November 17, 2025 at 9:32 am

Upgrade your Telegram experience with lingogram—AI‑powered tools for translation, smart replies, summaries, voice transcription, and more.https://intentchat.app

November 17, 2025 at 9:32 am

Transform any photo into a Studio Ghibli-inspired anime masterpiece with a single click—no software or design skills required.https://ghibliphotos.com

November 17, 2025 at 9:33 am

Snap any foreign-language menu and get instant AI translation, dish images, allergy filters, calorie info, and group-order suggestions.https://atmealtime.com

November 17, 2025 at 9:38 am

https://intent.app

November 19, 2025 at 12:39 pm

Nice blog i like it.

November 20, 2025 at 10:09 am

This article does a wonderful job breaking down the basics of stick figures and then showing you how to improve them step by step. The way it tackles common errors (like arms starting at the neck or legs branching out incorrectly) is super helpful — I especially liked the clear illustrations and the emphasis on keeping things simple yet accurate. If you’re beginner to figure drawing, this is a solid guide.

And if you work on video edits or creative clips too, you should totally check out soundboardMP3 — it’s full of funny, high-energy sounds that can make your videos way more fun and engaging!

November 22, 2025 at 3:13 am

https://vibeaha.com/ yes

November 22, 2025 at 7:18 am

Otakudesu is a popular anime streaming platform where viewers can watch the latest Japanese anime in smooth HD quality. It offers fast updates for ongoing episodes along with complete subtitle support for an enjoyable experience.

Fans can explore a wide range of genres and discover new titles all in one convenient place.https://otakudesu.pl/

November 22, 2025 at 11:27 am

Looking for Girls Partywear Dress online? We have multiple collection of babies Dresses, girls dresses, Party Dresses and Kids Fashion Clothing Online. Girls Partywear Dress

November 24, 2025 at 1:18 pm

This article effectively serves as a reminder that even the most difficult abilities, such as sketching the human body, begin with basic principles, and stick figures are an ideal starting point. The author simplifies anatomy and movement so that even novices may understand them. You can check out the Cineby App, a free streaming app (iOS version available) that provides a variety of informative and amusing video to enjoy while you practice your drawing fundamentals, if you’re seeking for more creative learning breaks or inspiration outside of painting.

November 24, 2025 at 5:02 pm

Bestehen Sie Ihre Requisitenfirma mit Leichtigkeit! https://propfirmpassnow.com/de/

November 25, 2025 at 5:59 am

thanks for sharing this post i love to read your blog

November 25, 2025 at 8:37 am

This is actually pretty cool! I always draw the most basic stick figures lol. Maybe I’ll actually try adding some of these tips and see if I can improve! It can’t hurt, right?

November 25, 2025 at 8:55 am

This is actually pretty helpful! I always struggled with making my stick figures look less awkward. Gonna try these tips next time I doodle. Thanks for the simple explanations!

November 28, 2025 at 6:11 am

Join the crazy Italian Brainrot meme universe in this wildly chaotic, free, unblocked clicker game—tap your way through an Italian-inspired Brainrot world, unlocking outrageous characters like Bombardino Crocodilo, Tung Tung Tung Sahur, Tralalero Tralala, Bombombini Gusini, and many more as you power up with insane upgrades. Dive deep into the viral clicker madness sweeping TikTok and YouTube, collect every hilarious creation, unlock wild mystery rewards, and dominate the world of Italian Brainrot Clicker today!

November 28, 2025 at 6:12 am

Labubu Wallpaper

November 28, 2025 at 6:14 am

Play the classic Google Color Tiles and discover more colorful puzzle games. Match colors, eliminate tiles, and challenge yourself with endless fun!

November 28, 2025 at 6:33 am

How to free use Flux 2

November 28, 2025 at 6:35 am

Greate! You create comfort and presence in the ways.

[Fish it!](https://fishit.cc)

November 28, 2025 at 6:37 am

Greate! You create comfort and presence in the ways.

[Raise Animals](https://RaiseAnimals.wiki)

November 28, 2025 at 6:39 am

Greate! You create comfort and presence in the ways.

[Nano Banana 2](https://banana2ai.com)

November 28, 2025 at 6:40 am