I’d like to preface this post with a brief acknowledgement of ignorance – I am not an expert on any of the subjects I’ll be discussing. I’m not a doctor, nor am I a professional artist.

I’m simply a curious amateur artist in the process of learning, attempting to explain these concepts in as simple terms as possible, while sharing with you my learning experience.

With that out of the way, let’s talk about the human skeleton.

Why is Understanding the Skeleton Important?

Well, for starters, it’s important to think logically when learning about complex subjects like human anatomy. Trying to memorize every single bone and muscle in the body, based purely upon their names and appearances, is not realistic.

There’s around 206 bones in an adult human, alongside over half a thousand muscles. Of course, not all of these are relevant for drawing – you don’t necessarily need to know about the smooth muscle found in your bladder and stomach (among other places) – but that’s beside the point.

It is much easier to memorize bones and muscles when you instead focus on learning their function. In terms of functional importance, our skeleton comes first, creating the structure of our body. Muscles come second, as a way for us to move that structure. When we move our bodies, we’re activating muscles which move our skeleton.

Think of it this way; without muscles, our body still has a structure. Looking at a skeleton, it’s still possible to observe the functions of our bones.

Without a skeleton, on the other hand, our bodies would be nothing – they would crumple under gravity and have no shape. We would just be a blob.

Although muscles play a very important role in defining the aesthetic of the human body (think bodybuilders), the skeleton gives those muscles their functions. Without a skeleton, our muscles are directionless and without purpose.

Our bones (skeleton) define the purposes of our muscles.

Why Should You Study the Skeleton Before Studying Muscles?

Honestly, whether or not you decide to study the skeleton first is entirely up to you. If you want to study muscles first, go right ahead.

HOWEVER, I think there’s certainly a valid case to be made that studying the skeleton first is more sensible, and (potentially) more beneficial.

Tendons and Attachments

Like I said, it’s important to think logically when learning about complex subjects like anatomy. To reiterate, our bones define the function(s) of our muscles, and give our bodies structure – but those are not the only things they do.

Our bones also tell us where our muscles attach. As I said in the previous section, when we move our bodies, we’re actually moving our skeletons by activating specific muscles. In order for that movement to be possible, our muscles have to attach to our skeleton, which they do through tendons.

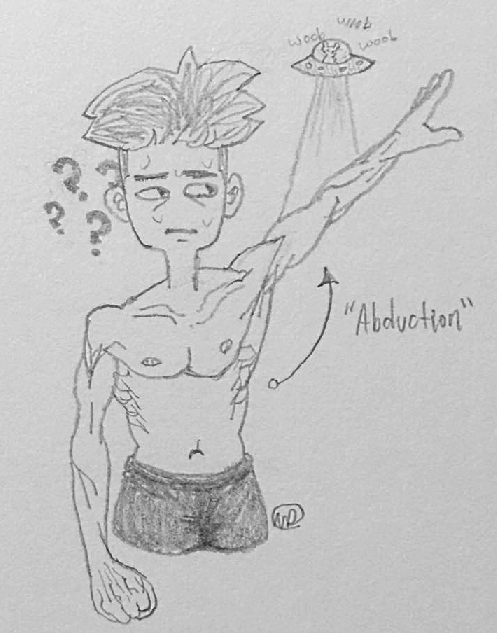

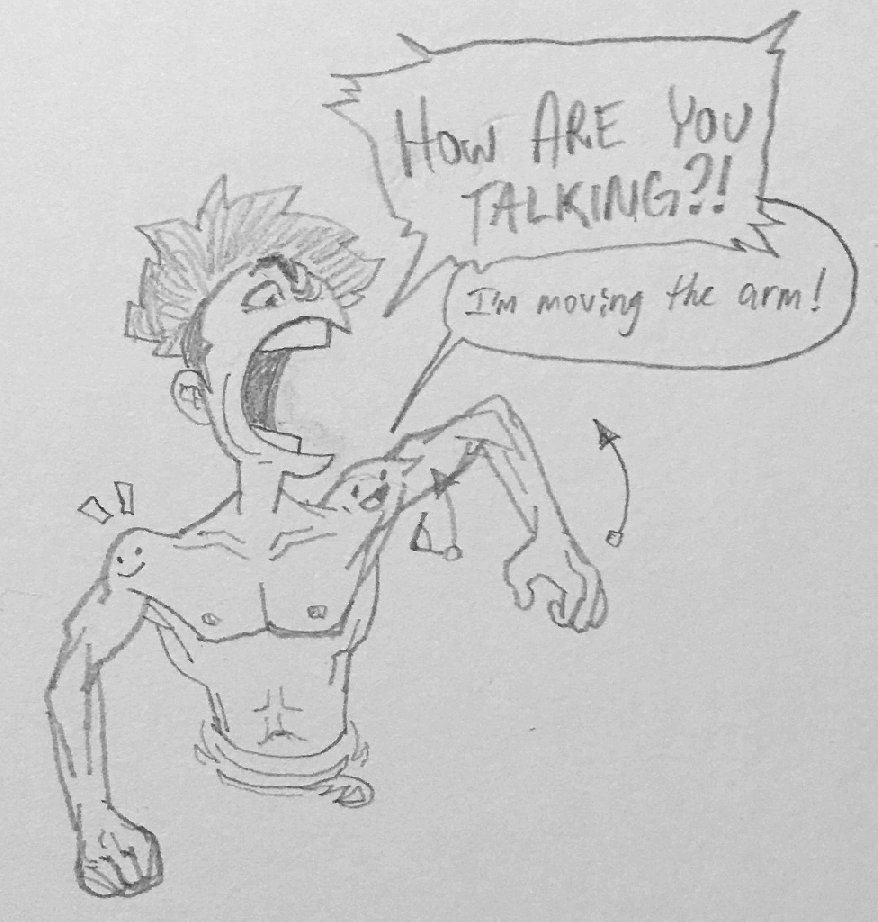

Your deltoid (shoulder) muscle, for example, is responsible for the abduction (raising) of your arm. Understanding that term in great detail isn’t especially important, just think of it like your elbow being pulled up and away (abducted) from your torso.

Some illustrations of abduction. The deltoid is not the only muscle that performs this type of movement.

In order for your deltoid to move your arm, it has to attach to your skeleton. Your deltoid attaches to your humerus (upper arm bone), about halfway down the length of the bone. Try feeling it for yourself!

Boney Landmarks

In addition to providing intuitive references for the functions and attachments of muscles, many skeletal structures serve as visual reference points, known as “boney landmarks.” This term is used to define bones visible on the surface of most peoples’ bodies.

The clavicle (collar bone), for example, is instantly recognizable and beneficial in creating a believable structure around the upper chest/lower neck area. (You can see it in both of the previous doodles related to the deltoid.) The same goes for the olecranon (elbow) and scapula (shoulder blades).

Simplicity in Quantity, Proportion, and Layers

As previously mentioned, we have far fewer bones in our bodies than we do muscles – and again, it’s not necessary to memorize all of them. Regardless, the smaller number of bones helps make the task of learning their names and functions more digestible.

Along with the higher quantity of muscles comes a greater degree of variance between said muscles’ appearances. As a result, bones are often a better (or simpler) measure of proportions – in my experience, at least.

Muscles vary drastically in size and shape. There’s rounded semicircle-esque muscle groups like the deltoids, broad, flat muscles like the latissimus dorsi, and even rhombus-shaped muscles, like the.. rhomboids.

In contrast, bones are generally a bit simpler – although that’s not always the case, of course. The pelvis, for example, can be an absolute nightmare to draw from certain angles.

In any case, bones are a very powerful tool for determining proportions. Since they tend to vary slightly less in size and shape (most of them are big and long), it’s easier to compare their sizes to one another.

You need not look any further than the standard unit of measurement in figure drawing, 1 Head, which is based upon the size of a skull.

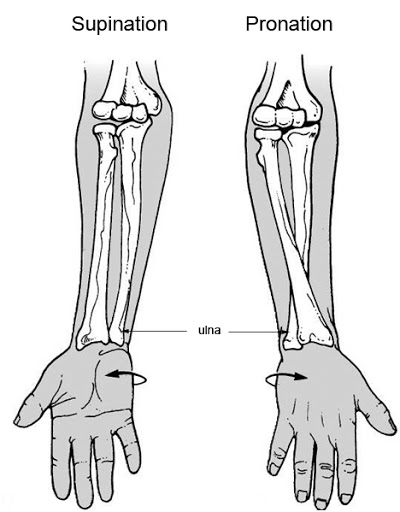

Lastly (and perhaps most importantly) is the difference in layering. Generally speaking, bones don’t have many layers, and when they do, it’s often possible to see both bones quite clearly, like when the radius and ulna overlap.

Even though the radius overlaps the ulna, we can still see both of them quite clearly.

In contrast, muscles can connect to bone in several different ways, and most sections of the body will be made up of several complex layers (deep to superficial), which overlay atop one another. Some muscles can be extremely difficult to see, while others are practically invisible from the exterior of a body (visibility varies depending on muscle definition). In the case of back muscles, there’s somewhere around 3-5+ layers of muscles which overlap and obscure each other.

This is true for most muscle groups, which makes learning and understanding them quite difficult – it’s tough to remember which muscles exist within each layer.

So… How Do I Learn About the Skeleton?

That, my friend, is not a question I’m qualified to answer. Although I’ve already written quite a lot – probably more than most of you are willing to read – I’ve really only scratched the surface.

The human skeleton is an extremely complex subject with lots of intricacies and minutiae. There’s the different types of joints (synovial, cartilaginous, fibrous, etc.), anatomical terminology which serves to define the orientation(s) of bones, muscles, and their movements (anatomical position, medial/lateral, etc.), the various ligaments and connections between bones, and even the specific functions of individual bones or bone structures (thoracic cage, spinal column, etc.).

Fortunately for you, if you’re interested in learning about human anatomy and/or how to draw it, there’s plenty of resources created by people far more qualified than me in both the fields of art, and anatomy. There’s books, YouTube videos, YouTube series, blog posts, and more.

I’ll be discussing some of these resources throughout the duration of this blog, so make sure to stay tuned!

And as always, thanks for reading.

Sources

Disclaimer

All information in these posts is my own words, unless explicitly stated otherwise. None of this information is quoted, nor paraphrased, unless explicitly stated otherwise. Any similarities between my own words, and the informative sources/hyperlinks provided is purely coincidental, unless explicitly stated otherwise.

In any case where I am using someone else’s words (or imagery), the source will be cited internally, with a link to that source provided either within the internal citation, at the end of the post under “Sources,” or both.

February 23, 2021 at 10:28 pm

Hi Makai! This is so interesting, especially from the perspective of someone like me who as absolutely no experience or skill in visual art. I have never considered that artists think about the anatomy of the people they’re drawing, but it makes total sense! Excited for the next post!

February 24, 2021 at 8:06 pm

I’m glad to hear it! I hope the post wasn’t too dry – I’ll be making an effort to make the content digestible for those who aren’t active/interested in visual art.

Yep, anatomy is a very important part of drawing the human figure. Even artists who create post-modern, hyper-stylized and abstract renderings of a person likely have some foundational knowledge of anatomy. Like Picasso said, “Learn the rules like a pro, so you can break them like an artist.”

Thanks for reading!

October 28, 2025 at 6:25 am

ok thank camel live

October 28, 2025 at 6:26 am

ok hesgoal

February 26, 2021 at 4:07 am

Hi Makai,

It’s so interesting to read about this as I took lots of anatomy classes throughout high school and now I’m more interested in the art world. I never really thought about the research artist have to put in to create their work, but I suppose it’s kind of like how mystery novelists have to research real true crime stories for inspiration. Excited to read more.

February 26, 2021 at 8:18 pm

Yep, it’s important to understand the things that you’re drawing. For one, it makes things easier to remember – if you know the function of a muscle, you’re less likely to forget about it, because you will understand that a body cannot function properly without it. For another, having a deeper understanding of a subject matter will allow you to more freely manipulate that subject in your art.

Even Kim Jung Gi says, “It is important to draw a lot.. but I believe understanding what you’re drawing is more important.”

February 27, 2021 at 10:20 pm

I never thought to connect knowledge of the human body to improve drawing, but it makes sense. Most Artists need a reference to what they are creating. Great drawings, they are a good comedic way to engage the reader.

February 28, 2021 at 8:25 pm

It’s a very easy thing to overlook, but like you said, it makes a lot of sense once you think about it.

I mean, imagine how difficult it would be to draw the underside of a car without knowing anything about the mechanics of an automobile. It would be practically impossible. A mechanic, on the other hand, even one without any drawing experience, would at the very least be able to draw the basic shapes that represent specific parts, because they would have a more developed knowledge of vehicular components.

I’m glad you like the doodles – drawing myself is sort of my comfort zone. Thanks for reading!

February 28, 2021 at 3:09 am

As an artist, I can say human anatomy isn’t the easiest thing in the world to depict in drawings. I myself practice drawing the human figure, however, I have never thought about studying the human skeleton before the muscles. When I practice drawing I feel like I focus/study more on muscles. This post is inspiring me to dive more into the human skeleton and how it supports and works with the muscles. Overall, this is a great topic for aspiring artists and I would like to mention I love the drawings you incorporated in the post and your overall artstyle!

February 28, 2021 at 8:17 pm

I think that’s a pitfall most artists can relate to (myself included). When I first started to take drawing seriously, I did lots of figure drawings, and didn’t pay much attention to bones, because for the most part, they’re not visible. Like I mentioned in this post, there are some bones that most of us are probably familiar with (collar bone, shoulder blades, ribcage, etc.), but it’s easy to underestimate the importance of them in art.

It’s kind of like building a house – you can’t just jump right into laying down drywall without some sort of wooden frame, (I mean.. maybe you could, but you probably shouldn’t). I definitely recommend studying the skeleton, it makes drawing the human form feel a bit less overwhelming.

April 8, 2024 at 8:55 pm

I’d like to preface this post with a brief acknowledgement of ignorance – I am not an expert on any of the subjects I’ll be discussing. I’m not a doctor, nor am I a professional artist.

I’m simply a curious amateur artist in the process of learning, attempting to explain these concepts in as simple terms as possible, while sharing with you my learning experience.

April 8, 2024 at 9:03 pm

Coffee is part of so many people’s lives nowadays and many people start their day with a cup of coffee. Coffee is what can make a difference in a lot of people’s moods.

May 29, 2024 at 7:04 pm

I appreciate the efforts you people put in to share blogs on such kind of topics, it was indeed helpful. Keep Posting! percetakan 24 jam

August 6, 2024 at 6:01 am

I really like your idea. I hope you will visit my website Tempat Print Murah Jakarta Timur

August 25, 2024 at 11:13 am

Thanks for it.

araç proje

September 4, 2024 at 8:57 am

Sharing of information is excellent. Thanks for providing us with the opportunity to read this post; I’m glad I did. extremely nice This article is very helpful.

https://www.axaprinting.com/

September 4, 2024 at 12:52 pm

I love your article, thank you percetakan 24 jam jakarta

September 9, 2024 at 8:42 am

Thanks for writing this nice article.. Anyway, I’m going to subscribe to your rss and I hope you write great articles again soon. cetak buku cepat rawamangun

October 1, 2024 at 9:43 am

keep sharing, make other people happy, and good luck always

Jasa Scan Dokumen Murah

October 1, 2024 at 2:56 pm

Very good article! Anyer Printing

October 5, 2024 at 4:04 pm

good job post , thank you.

cetak stiker polyfoam 24 jam

October 9, 2024 at 1:13 pm

The skeleton is very important… I really like the pencil drawing… very interesting and looks natural.

BISAJITU HOKKI TOTO SEMAR

October 10, 2024 at 3:10 pm

nice information, i like your artucle

Percetakan murah Jakarta

October 23, 2024 at 4:00 pm

Visit our website to serve all printing and digital printing needs with maximum results

November 16, 2024 at 8:45 pm

Nice information. Animals lover! I love animals

November 27, 2024 at 9:19 pm

Cetak Stiker foamboard

January 2, 2025 at 12:28 am

Discover the art of printing with us, where every detail is meticulously crafted to make your projects stand out and shine.info link

January 31, 2025 at 11:38 am

Wow that is the best content ever for the same engagement with day to all my dear friends and friends and friends and friends

February 26, 2025 at 5:59 am

The article I’ve been looking for, thank you

April 4, 2025 at 6:34 pm

The article I’ve been looking for, thank you

April 4, 2025 at 6:35 pm

thank you pauxe

April 4, 2025 at 6:37 pm

thank you egemenlik

April 4, 2025 at 6:38 pm

thank you zip code vfuq

April 4, 2025 at 6:39 pm

thank you template top html

April 4, 2025 at 6:39 pm

thank you skor oyun games

April 7, 2025 at 3:37 pm

By using local directories, international firms can identify potential Turkish partners, understand regional markets, and establish strong local relationships.

April 8, 2025 at 1:43 pm

You can trust us to perfect your website with important elements like user-friendly interface, responsive design, fast loading times and SEO optimization.

April 22, 2025 at 5:07 am

The article I’ve been looking for, thank you

May 12, 2025 at 1:55 pm

Really enjoyed reading this post! It’s always inspiring to see how students and faculty are creating meaningful experiences on campus. Thanks for sharing such valuable insights!

May 13, 2025 at 3:08 pm

Greetings with me from the online game site from Indonesia HIDUPJITU .

May 25, 2025 at 6:52 pm

wow…. the article is really helpful Jilid Hard Cover Murah

May 30, 2025 at 11:47 am

Adana avukat ile adanada en iyi avukat ceza avukatı, aile avukatı

July 22, 2025 at 9:58 am

Best!

Danke Digital olarak; web tasarım, sosyal medya reklamcılığı, Google Ads, SEO ve yapay zeka destekli yaratıcı çözümler gibi birçok alanda markalara özel çözümler üretiyoruz.

July 31, 2025 at 2:44 pm

Instantly calculate your earnings for any pay period with our simple and accurate hourly paycheck calculator .

August 3, 2025 at 8:36 am

Visit our website

August 20, 2025 at 7:56 am

Players are encouraged to try out bloodmoney various tactics, equipment, and disguises until they discover a look that suits them best because the game promotes originality

August 25, 2025 at 4:44 pm

Thanks for sharing your learning journey! I found your honest take on struggling with the human skeleton as an amateur artist really relatable and helpful for beginners like me.

August 25, 2025 at 4:45 pm

I totally relate to the struggles of studying anatomy for art! It’s tough but so rewarding. By the way, I’ve been using bypassgpt to make my AI-generated content feel more human and natural, which helps a lot in learning.

August 25, 2025 at 4:45 pm

Great post on learning anatomy for art and games! It’s tough but rewarding. By the way, for more game dev resources, check out bloodmoney—it might help with your projects.

August 29, 2025 at 4:33 pm

Thanks for sharing your learning journey! I found your honest take on studying the human skeleton as an amateur artist really relatable and helpful for my own art projects.Yes No Tarot

August 29, 2025 at 4:35 pm

I really enjoyed your post on drawing the human skeleton—it’s so relatable as an amateur artist! Sometimes I wish I had guidance like that, maybe even from something like Yes No Tarot for quick answers in life.

August 29, 2025 at 4:37 pm

I really enjoyed your post on drawing the human skeleton—it’s so relatable as an amateur artist! Sometimes I wish I had guidance like that, maybe even from something like Yes No Tarot for quick answers in life.

August 29, 2025 at 4:40 pm

I loved your insights on studying the skeleton for art—it’s so relatable! Sometimes I wish I had a quick way to make decisions, like using Yes No Tarot for guidance on what to draw next.

August 30, 2025 at 10:18 am

This blog information is very amazing myaarpmedicare

September 18, 2025 at 7:19 am

If you love Clash Royale and enjoy puzzle-solving Royaledle is your new obsession. It’s a daily dose of strategy and fun that never gets boring!

October 3, 2025 at 1:39 am

To really master these skills, players need to Melon Playground practice and be creative so they can learn when and how to use them best.

October 4, 2025 at 3:39 pm

I really enjoyed your post about drawing the human skeleton! It’s tough to get the anatomy right. Sometimes I use tools like sora2 video to see animated references, which helps a lot with learning.

October 4, 2025 at 3:40 pm

I really enjoyed your post on drawing the human skeleton. It’s tough to get the anatomy right! For tricky poses, I’ve found tools like Wan Animate super helpful for visualizing movements in art and game projects.

October 15, 2025 at 11:01 am

Wheon GTA – Your Grand Theft Auto Universe Wheon Games Wheon Games wheon grand theft auto

October 16, 2025 at 3:37 am

I completely agree with your insight about the connection between bones and muscles. I remember when I first started studying anatomy; it felt overwhelming at first. However, once I grasped how everything links together, it made learning much more enjoyable. Understanding these connections truly deepens our appreciation for how our bodies function! Geometry Dash

October 26, 2025 at 1:32 pm

Agreed with your article! Baju Kurung Pahang

October 27, 2025 at 8:30 am

To draw human bones I think it is very difficult and requires specialized artistic skills to make it easier. Play: geometry dash subzero

October 31, 2025 at 3:43 pm

Sora 2

Create stunning videos with Sora 2, OpenAI’s advanced AI video generator. Generate high-quality sora 2 videos from text with synchronized audio by Sora AI.https://forvideo.ai/sora2

November 5, 2025 at 5:26 am

This blog information is very amazing E-ZPass Illinois

November 24, 2025 at 3:51 pm

Aged paper and document effects from Nano Banana Pro show authentic yellowing and texture degradation over time.

December 4, 2025 at 6:18 pm

Loved the points you made here. https://7yuehory.icu/

December 9, 2025 at 10:36 am

Thanks for the tips! https://t618hgv.icu/

December 16, 2025 at 8:19 am

Studying the human skeleton is Bloodmoney one of the most challenging parts of learning how to draw the human figure. From memorizing bone proportions to understanding how joints move, artists often struggle to turn anatomy knowledge into confident, accurate drawings.

December 21, 2025 at 4:27 pm

MyAARPMedicare is an online portal and website provided by AARP (American Association of Retired Persons) for individuals who are enrolled in Medicare Advantage or Medicare Part D plans.

December 24, 2025 at 5:24 am

thank you

December 29, 2025 at 6:53 pm

jogo do corinthians ao vivo – https://jogo-do-corinthians-ao-vivo.com