Please be aware this post contains content considered harmful, offensive, and inappropriate in contemporary settings. The University Libraries strive to create an accessible, welcoming, and accountable understanding of the historic record.

With Homecoming just around the corner, Willie Warhawk will be busier than ever. Today, the name Willie Warhawk is iconic on UW-Whitewater’s campus in reference to the university’s Warhawk mascot. Yet, how did Willie get his name? The answer to that is not so clear and straightforward.

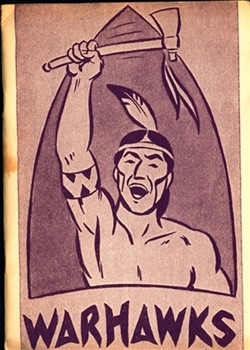

The name Willie has been associated in some form or another with the Warhawk mascot since at least 1963.[1] At that time, the school’s symbol was a Native American ‘Warhawk’ warrior. A contest was held on campus in 1958 to select a symbol representing the university. The Native American Warhawk warrior was selected as the winning entry because this was “historically Indian country, [and] the Warhawk seemed to be symbolic of the early fighting spirit” of the Native American warriors in this territory.[2]

During the 1960s and early 1970s, the name Willie was used in reference to the Native American warrior, a cherub-styled symbol of that warrior, and as the name of a spirit award for seniors.[3] Despite adopting the Native American warrior as the school symbol, it was not the official mascot, which allowed for variations. In 1963, it was one of the variations, the mini-version of the Native American symbol, when the name Willie was first documented. It was used as part of the 1961 Homecoming promotions and campaign. This version was so popular that it was featured numerous times in the Royal Purple in the following years for advertising purposes and was even a contender in the eyes of some to become the school’s mascot.[4] Over the next few years, the name Willie became the ‘official’ name for the Warhawk in all its forms, thus giving us our first iteration of “Willie Warhawk.”

By the 1970s, there was a call for changing the university’s symbol from within and outside the campus community to something more culturally sensitive.[5] A competition was held for students to send in submissions for a new university emblem. In the fall of 1972, a hawk was chosen as the winner. [6] While the flying hawk was now the university’s official symbol and, therefore, did not necessitate a name change, the Native American image was still used as a logo for the athletic programs for years.[7]

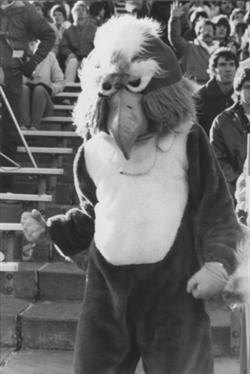

Despite selecting the flying Warhawk as the new symbol, it wasn’t until 1982 that the university adopted it as the official mascot.[8] To celebrate, the cheerleaders, at halftime during the Homecoming football game in 1983, held a “Name the Warhawk” contest.[9] Unfortunately, the results of this contest were not officially documented. While we have no official results from the contest, the name Willie, starting in 1983, was used in reference to the new Warhawk mascot, giving us our modern “Willie Warhawk.”

While we have no official documentation as to how the name Willie first began to be associated with a symbol of the university, it’s a name we know and love today. Willie Warhawk can be found all over campus at events and in many forms, from plushies to bobbleheads. Keep your eyes peeled for Willie Warhawk during the upcoming Homecoming events!

[1] “Take Home a College Souvenir,” The Royal Purple, May 21, 1963, https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.32934854

[2] “’Warhawks’ Is Announced As WSC Athletic Symbol,” The Royal Purple, April 22, 1958, https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.32716935.

[3] “Spirit Campaign Begins,” The Royal Purple, October 15, 1968, https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.32935055; “Most School Spirited Senior Awarded,” The Royal Purple, March 17, 1969. https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.32935087.

[4] Eleanor Kilmek, “About a School Mascot,” The Royal Purple, October 29, 1963, https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.32934868.

[5] “Stevens Point Senate Opposes ‘Warhawk,’” The Royal Purple, May 9, 1972, https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.33158337; “’Willie Warhawk’ Discriminates Against the Indians on Campus, “ The Royal Purple, March 16, 1977, https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.33158473.

[6] “Flying Hawk Sports Emblem,” The Royal Purple, September 26, 1972, https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.33158341.

[7] “’Willie Warhawk’ Discriminates Against the Indians on Campus, “ The Royal Purple, March 16, 1977. https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.33158473.

[8] “”Son’s Toy Hatches Willy,” The Royal Purple, October 22, 1997, https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.34305705.

[9] “Cheerleaders Conduct Name Mascot Contest,” Minneiska, 1983, UW-Whitewater Archives and Area Research Center, 166.