A natural way to think about the meaning of a word is to break it down into its parts, something technically different from breaking a word itself into its parts. The latter case is, for example, the breakdown of a word like “unrecyclable” into the listemes un-, re-, cycl(e), and –able. Listemes, in turn, can be dissected according to their semantic contents. Take for instance, the listeme “girl.” The semantic parts that comprise this listeme include the notion of femaleness, humanness, and youth. Linguists have tried to formalize these semantic parts, not without some considerable controversy. One proposal is that all semantic parts come from a limited set of semantic features that we have stored in the mind, and that are part of our genetic endowment. These semantic features are posited to be the basic, binary stuff out of which all complex meaning is created.

Returning to our example of ‘girl’ above, we might formalize its semantic parts as features consisting of at least the following: ([-male], [+human], [-mature]). We would interpret this formalization as follows: the listeme ‘girl’ is comprised of three binary semantic features: it is negatively specified for the semantic features [male] and [mature], meaning that ‘girl’ is not a male and not someone who has reached the age of full maturity; conversely, it is positively specified for the semantic feature [human], meaning that ‘girl’ is a person and not another kind of animal.

Maybe this formalization process looks a little ugly to you, but there are many exciting dimensions of thought that it opens up. Ultimately, a test of its value is its usefulness in explaining things. One thing that any semantic theory should be able to explain is the idea of synonymy. With our formalization, we could suggest that words like ‘girl’ and ‘miss’ are synonyms in that they are each comprised of the same semantic features, that is both are ([-male], [+human], and [-mature]). Antonymy would arise whenever two words are alike in all there semantic features except one: so ‘girl’ would be an antonym with ‘boy’ because ‘boy’ would have all the semantic features of ‘girl,’ except that it would be positively specified for the feature [male]. On a different dimension ‘miss’ differentiates itself as an antonym to “Mrs” in a specification that we might call [mate]; thus, ‘miss’ and “Mrs” are alike in all features except that “miss” is [-mated] while “Mrs” is [+mated].

Exploring further relationships, we could say that one word is a “hyponym” of another word if it contains all the semantic features of the other word, and then some. So, for example, “girl” is a hyponym of “youngster” because in order to specify “girl” you need all the semantic features ([+human], [-mature]) that are needed to specify “youngster.” Conversely, we could call “youngster” a “superordinate” of “girl.” Hyponymy can be differentiated from concepts like overlap in ways that I will let you explore on your own.

There are some exciting philosophical implications of this model for understanding lexical semantics: words are formed from connecting already present semantic features; one result is that very complex results can be established in next to no time: Consider a word like “persuade,” used by children of any language at early ages without specific instruction. Its meaning is actually wonderfully complex, as it can be broken down into something like . . .

‘to cause someone by means of the process of disputation to do something which is successfully accomplished, and accomplished voluntarily and not through any act of coercion.’

Because these semantic features can be quite complex, humans learning a human language will learn something like the concept “rabbit” long before fathoming the ostensibly identical “undetached rabbit parts.” That is, words will come in the form of well-defined “parts,” not any old conceivable piece of a word will be able to make up a part.

Conversely, just as we are designed by our genetic endowment to package the world in certain ways, it follows that there will be a whole universe of possible intellectual conceptions that are in principle impossible for human beings to conceive. Of course, these impossible conceptions are difficult to fathom because they are by definition unfathomable. Perhaps certain mathematical concepts point us in the direction to look. Here we have concepts that we are led to posit by a logical process, even if the concepts themselves are unfathomable . . . I’m thinking of notions like “instantaneous change” (fundamental to Calculus), “imaginary numbers” (like the square root of negative one), and “quant” (a physical unit that is neither mass nor energy).

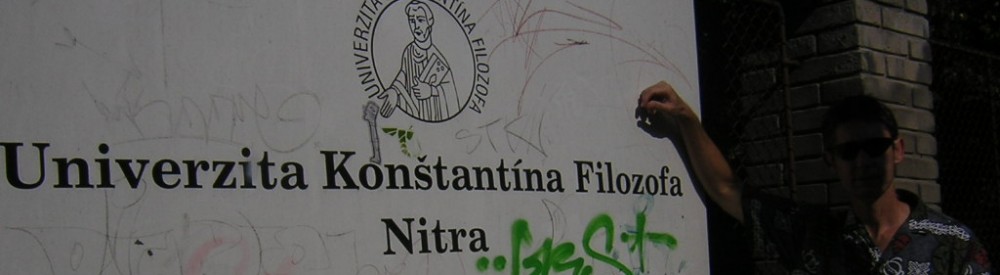

Like many places in Slovakia, Nitra has its share of ‘public art,’ expressed in all the advertisements, instructions, graffiti, and ubiquitous tagging of buildings, trains, bridges, fences, in short, anything that represents a potential canvas, something that can be seen by the random passers-by. So I wasn’t so surprised when a sidewalk in our fine city’s Stare Mesto neighborhood greeted me last week with the banner “Milujem ťa.” Of course, its full meaning is as inscrutable to me as the tags surrounding me as I walk through any underpass.

Like many places in Slovakia, Nitra has its share of ‘public art,’ expressed in all the advertisements, instructions, graffiti, and ubiquitous tagging of buildings, trains, bridges, fences, in short, anything that represents a potential canvas, something that can be seen by the random passers-by. So I wasn’t so surprised when a sidewalk in our fine city’s Stare Mesto neighborhood greeted me last week with the banner “Milujem ťa.” Of course, its full meaning is as inscrutable to me as the tags surrounding me as I walk through any underpass.