Frequently we talk about a “standard version” of the language. What is “Standard English”? This question is especially tough to decide, with respect to English, because it is a native language in widely dispersed areas. What version of English do you think is “standard”? Perhaps it is easier to think about what makes a particular version of a language “standard.” Florian Coulmas, in Chapter Two of his book Sociolinguistics: The Study of Speakers’ Choices, points to the connection between what is considered the standard form of the language and the notion of social prestige: the standard form of the language will be the form used by the most prestigious class of society. But then the question becomes that of determining or identifying class distinctions. In the United States, “Standard English” is sometimes described as “Network English”—the type of English that is used by news commentators on the national television networks. In terms of the various dimensions according to which language may vary, it can be described as the variant of language associated with the region of the upper Ohio River Valley, so-called North Midland American English. Let’s say that Columbus, Ohio, is its epicenter. Columbus is basically white, professional (home of a big University, Ohio State University), economically vibrant, somewhat younger-than-average population, with a moderate to conservative political base. It is at the center of a band that stretches across the United States from Philadelphia out to Omaha, Nebraska. This swath extends north to Cleveland, Chicago and Minneapolis, and south to Indianapolis and St. Louis. You can also hear Standard American English in the voice of “Directory Assistance” on our telephones, or in our commentators on National Public Radio. The written Standard of American English can be seen in high school textbooks, Newsweek Magazine, or the New York Times newspaper. It has wide currency in printed material virtually throughout the US.

When we take a broader perspective, it becomes harder to talk about “Standard English.” Obviously the American Standard does not hold for Great Britain, or Australia and New Zealand.

So let’s try to address some important questions: (i) from what perspective can we detect the “Standard” form of a language? (ii) What are some of the problems in identifying the social class with which the “Standard” is associated?

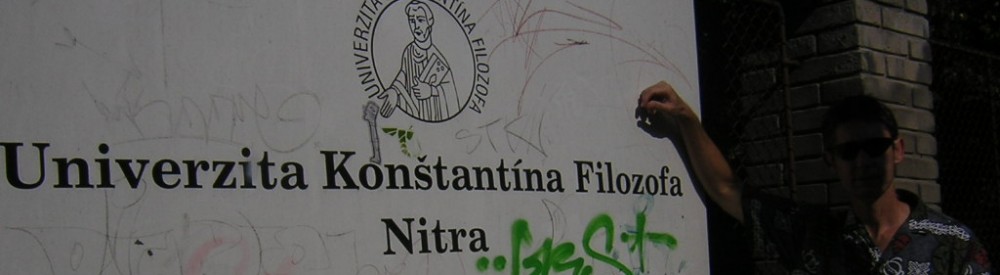

So far I have been writing about Standard English, but non-native speakers are at some disadvantage on this topic. Is there a standard form of your own native language? Until recently, Slovakia was part of a socio-communist state apparatus, at least nominally dedicated to eliminating social and economic inequality. Under such conditions, was it still possible to identify social classes in Slovakia? What were they?