Last week we spent some time thinking about the little Slovak word “no,” which turns out to have a very far-reaching and subtle range of significance. Words can be broken down into what linguists call “function words” and “content words.” Now this is a simplification, but the significance of function words is to organize the flow of information of the expressions in which they occur. Consider the following sentence pair:

(i) John was fond of Mary

(ii) John was found by Mary

If we try to explain the significance of the words “of” and “by,” we might have some problems, especially if we think only of dictionary definitions. It would be far easier to reflect on how they function rather than what they mean, and much more productive, practically speaking! In the first sentence, “of” functions to link “Mary” to “fond” as its object. That is, the relationship between “fond” and “Mary” and “John” is identical to what we have in the following sentence:

(iii) John likes Mary

In comparison, “by” in (ii) tells us that “Mary” is linked to “found” as its subject, and that “John” should be interpreted as the object of the action of the verb, just as in (iv):

(iv) Mary found John

Returning to Slovak “no,” we can see that it works on a variety of functional planes. Signifying either affirmation or negation, it has an almost mathematical formulation: it is an ‘operator,’ specifically, a “polarity item” (+/-) which tells how the associated expression is to be taken. We also saw Slovak “no” signify something close to ‘but,’ another organizational concept, linking two grammatically identical but semantically variant expressions into a compound structure.

Other instances of Slovak “no,” where the English translation would be something like “well,” showcase the “modal function” of the word, where ‘modality’ can be summarized as reflecting the speakers’ feelings about the associated expression.

Contrasting with function words, content words carry the lion’s share of the specific information in expressions in which they occur. But what exactly is their “content”? As we attribute definitions to the content words of our language, how do we account for relationships that exist among them? Why are “hot” and “cold” opposites, but not “lollipop” and “diagonal”? How are “cause” and “coerce” related? And do “boy” and “lad” really mean the same thing?

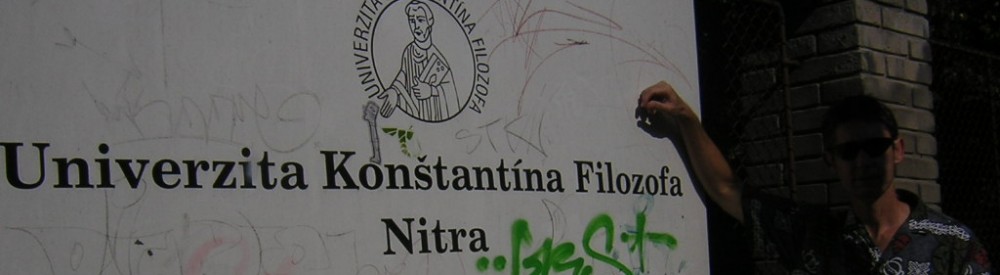

At the top of this essay is a photo of a t-shirt that I’ve been wearing around Slovakia. What is it that caused someone—the creator of this t-shirt—to select these words in particular? Why do Slovaks often laugh at me when they notice what is printed there? What can we glean about the nature of ‘meaning’ by thinking about other words that would be appropriate for this shirt. I suspect that these might be candidates: “burčiak,” “žinčica” . . . . Can you think of others?